Unkei (c. 1150–1223) was centuries ahead of European wood carvers. The Japanese sculptor was the very first to introduce expression in the faces of his sculptures. He also already worked under his own name, while the European makers of Christ and Mary sculptures still delivered their work anonymously at the same time.

Unkei was centuries ahead with the expressive expression on the face of the priest Muchaku.

Unkei belongs to the exceptional artists from the Middle Ages of whom not only the work, but also the name has been preserved. He lived and worked in a time of political instability and social change. Power in Japan shifted from the imperial court to the military class of the samurai. In this context Unkei developed a visual language emphasizing physical presence, emotional intensity and a striking sense of individuality.

At the time of the Samurai

He was born around the middle of the twelfth century as the son of a prominent sculptor. This studio played a central role in the restoration of temples and sculptures after the devastation of wars. Within this workshop Unkei learned the craft of Buddhist wood sculpture, but he would soon develop his own signature.

His earliest dated work, a seated Dainichi Nyorai from 1176 in the temple Enjō-ji, still shows the formal calm of the tradition of that time. Yet in the sculpture Unkei’s interest in inner concentration is already present.

In the first decades of the thirteenth century Unkei reaches his full maturity. His monumental sculptures are no longer timeless icons, but seem to breathe, to react tensely. The famous Niō guardians at the Great South Gate of Tōdai-ji in Nara, realized in 1203, are the most impressive example of this. These wooden figures, more than eight meters tall, show tense muscles, contorted faces and a physical power that directly confronts the visitor. The sacred is not elevated here by distance, but by proximity. The wooden sculptures of over eight hundred years old were restored not long ago, in 1989.

Buddhist patriarchs

Perhaps even more radical are Unkei’s portrait-like sculptures of Buddhist patriarchs, such as Muchaku and Seshin in Kōfuku-ji. Here there is no longer any question of abstract holiness, but of individuals with a recognizable age, facial expression and inner life. Wrinkles, sunken cheeks and a penetrating gaze suggest experience and spiritual depth. Unkei was clearly interested in the person behind the religious ideal. The sculptors in Europe around 1150–1223 were far from ready for that.

European wood carvers carved much later this Röttgen pietà, a milestone in Western cultural history.

In Europe in Unkei’s time the Romanesque Christ and Mary sculptures that strongly resemble each other dominate. The sculptures were carved anonymously in workshops by ‘Masters’. The sculptures are mainly frontal, strictly stylized and focused on symbolic clarity. Emotion is subordinate to theological meaning. The maker disappears behind the craft; the name does not matter. That Unkei’s name was passed down underscores his exceptional status as an artist avant la lettre.

For comparison: take the famous wooden Röttgen pietà from the early 14th century (approximately 1300-1325) that is now in the Landesmuseum in Bonn. It is a depiction in which Mary this time does not hold the ‘little child’ Jesus, but her adult son who died on the cross in her arms. It is a realistically carved sculpture, painted and intended to be placed on the altar, 87.5 centimeters high. Believers thus clearly received the message: suffer along with Mary, her pain is unbearable. Christ’s wounds are grotesque, like bullet holes, accentuated with red paint. The emotion is thus laid on thickly, but is not very subtle. Yet this work is considered a highpoint of European art history — and is actually mentioned in the art bible ‘Janson’s History of Art’, where wood carving art hardly receives attention — Unkei not at all.

Seshin, another lifelike priest, carved by Unkei.

Also in terms of expression Unkei is far ahead of his time. Where in Europe serious attention to individuality and psychological facial expression only arises from the Renaissance onwards, Unkei is already fully experimenting with it. His sculptures show anger, concentration, compassion and determination, not as abstract concepts, but as tangible human experiences. It is striking how modern this approach feels.

I make this comparison myself; I have not been able to find existing art historical sources for it. Art historians may not find this perspective interesting, or still focus too much on Western art history alone.

Japan was a closed world

There was no exchange of ideas between Japan and Europe at that time. Japan was then still largely a closed world. Japanese art seems to be discovered in Europe only around 1900, when artists like Van Gogh and Gauguin got an eye for the refined aesthetics of Japanese prints. They even began to collect the painted wrapping paper of Japanese goods and painted it. An early comparison between Japan and European wood carvers is thus uncharted territory.

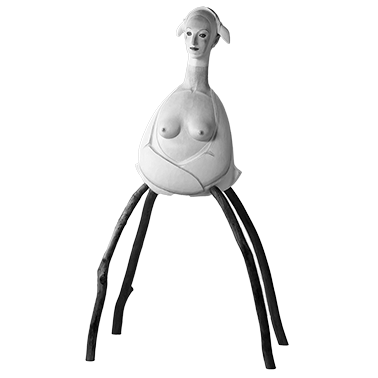

What is certain for me is that Unkei’s work shows that wood, in the hands of a master, can grow into a carrier of emotion, individuality and historical change. And 800 years later can still be a source of inspiration, such as for the Japanese artist Katsura Funakoshi. He even adopted the idea from Unkei who mounted glass eyes in his priest sculptures. Funakoshi did something similar, with marble eyes. The effect is the same: their sculptures seem to stare right through you.

Jan Bom, January 28, 2026