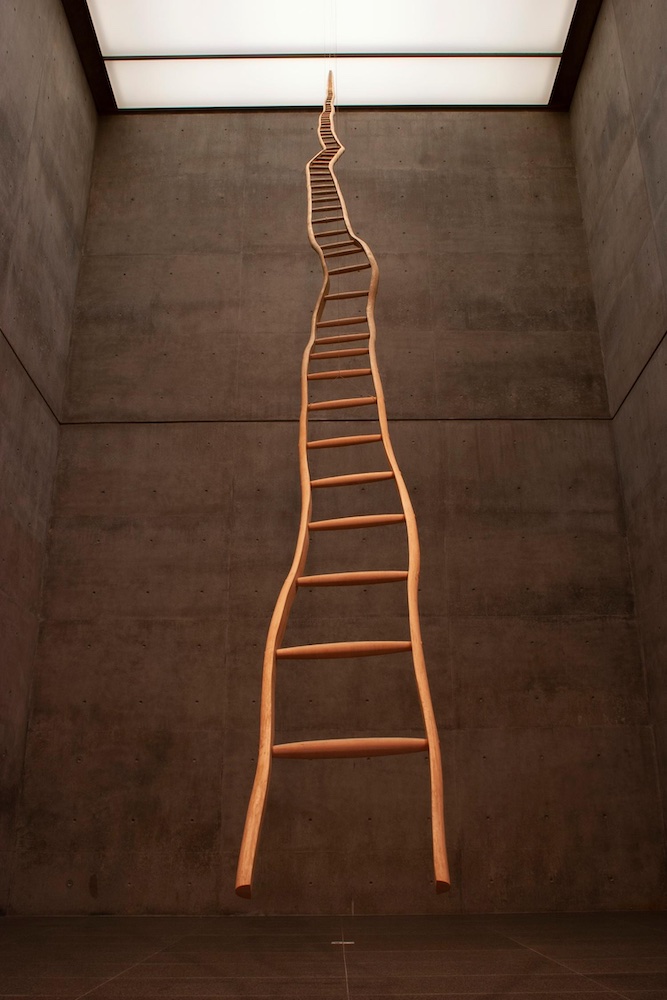

Martin Puryear depicts the social ladder as an endless climb. His wooden ladder of almost 11 meters gets narrower the higher it goes. The title Ladder for Booker T. Washington refers to one of the first Black African-American leaders. Puryear himself also comes from the Black community of the US.

Martin Puryear depicts the social ladder in his wooden construction Ladder for Booker T. Washington .

Wood is never just a material for Martin Puryear (1941). He chooses it carefully and works it with an almost meditative attention. His sculptures are often handmade, without visible mechanical interventions, even though they are sometimes monumental in scale. The traces of labor are not erased, but rather integrated into the final result.

Planing, bending, laminating, steaming and assembling: Puryear uses both traditional and self-developed techniques to give wood its specific form, without denying its natural properties.

A ladder of maple and ash

The skin of his sculptures is often smooth and closed, sometimes dark stained or patinated, giving the material something timeless and almost archaeological. At the same time, the structure of the wood remains tangibly present. Grains, tensions and curves determine the form, as if the sculpture was ‘found’ rather than made.

His famous ladder is made by joining two types of wood: maple and ash. It consists of a narrow, tall trunk connected with sturdy rungs. The split trunk has retained its natural, rugged shape. The rungs are perfectly worked into round spindles. The ladder of 10.97 meters is 58 centimeters wide at the base. At the top, the last rung is only 3.2 centimeters. A human foot no longer fits on it. The ladder has thus become ‘impassable’ at the end.

I find it a beautiful discovery to leave naturally formed wood intact and combine it with wooden spindles turned on the lathe. Puryear thus unites nature and machine.

Like a Jacob’s ladder reaching to heaven

In this sculpture Ladder for Booker T. Washington (1996) Puryear uses wood to evoke historical and political meanings without becoming explicitly narrative. The tapering ladder refers to social mobility, but also to its limitations. And not to forget: the finiteness.

But Puryear also plays a second game with perspective. By also suspending the ladder from virtually invisible plastic threads, an almost Biblical scene is created: like a floating Jacob’s ladder reaching to heaven. Puryear himself called this a ‘forced perspective’.

The symbolism is not difficult to guess, through this title, which he only conceived after completion of the work – he did that quite often by the way. The association with Booker T. Washington — the American educator and leader — can be read as a metaphor for progress and ambition under difficult circumstances. Washington embodied in his time the ideal of gradual social and economic progress, despite great social obstacles for the Black population.

He had even experienced slavery, as a young child. He was born in 1856, in the southern state of Virginia. His mother was enslaved; his father was presumably a white man who worked on the plantation. Washington was thus nine years old when in 1865, after the American Civil War, slavery was abolished. The ladder therefore does not refer to an abstract idea of progress, but to the literal historical leap from slavery to education, self-determination and social position — a climb that Washington himself had to make, step by step, under great limitations.

The ladder can be seen in the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in Texas, United States.

Trained in Sierra Leone and Japan

All in all, Martin Puryear belongs to the most respected American sculptors of his generation. The artist was born in Washington D.C. and grew up in an intellectually and culturally conscious environment. His father was a diplomat, his mother a musician. That combination of global orientation and discipline would strongly influence his later artistry.

After studies at the Catholic University of America and Yale University, Puryear left for West Africa in the sixties. In Sierra Leone he worked as a volunteer and learned traditional woodworking techniques from local craftsmen. This experience proved crucial: here he came to the lifelong conviction that conceptual depth and craftsmanship mastery are not opposites, but rather reinforce each other.

Hidden connections

After his time in Sierra Leone, Puryear also immersed himself in Scandinavian wood traditions in Sweden, which further sharpened his sensitivity to form and material.

In Japan Puryear finally immersed himself in Japanese wood construction and craft traditions, particularly in the way wood is joined without visible connections. The attention to internal construction and ‘hidden logic’ in his sculptures is often linked to these Japanese traditions.

The attention to craftsmanship alone makes Puryear someone who forced a breakthrough: the art world looked — and looks — down deeply on this, or considers craftsmanship skills as something from a distant past. Especially after World War II, abstraction was the norm, also in art education. It is therefore a miracle that the failing art bible Janson’s has paid some attention to his work.

Museum Voorlinden in Wassenaar also showed the formidable craftsmanship skills of wood artist Puryear.

Although Puryear is often labeled as ‘post-minimalism’, he distinguishes himself from this by his warm materiality. Where minimalist sculpture is often industrial and distant, Puryear’s wood remains tactile and human. It carries traces of time, labor and attention. Precisely therein lies the power of his work: it connects formal abstraction with cultural memory and bodily experience.

Carrier of silent meanings

Martin Puryear lives and works in the United States. He was honored in 2019 with a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His oeuvre shows how wood, if treated with knowledge, respect and imagination, can grow into a carrier of silent but deep meanings. Museum Voorlinden also exhibited work by Puryear in 2018.

In summary: Puryear forces the viewer to look up, but denies them the possibility to climb — a sculpture that shows ambition without the promise of fulfillment.

Jan Bom, January 26, 2026