Bruno Walpoth honors the vulnerable human, huddled, turned inward, closed off from the outside world. By painting his sculptures with white primer, the life-sized sculptures also appear as shadows of themselves. These characteristics make Walpoth one of the most famous representatives of contemporary wood carvers from Val Gardena.

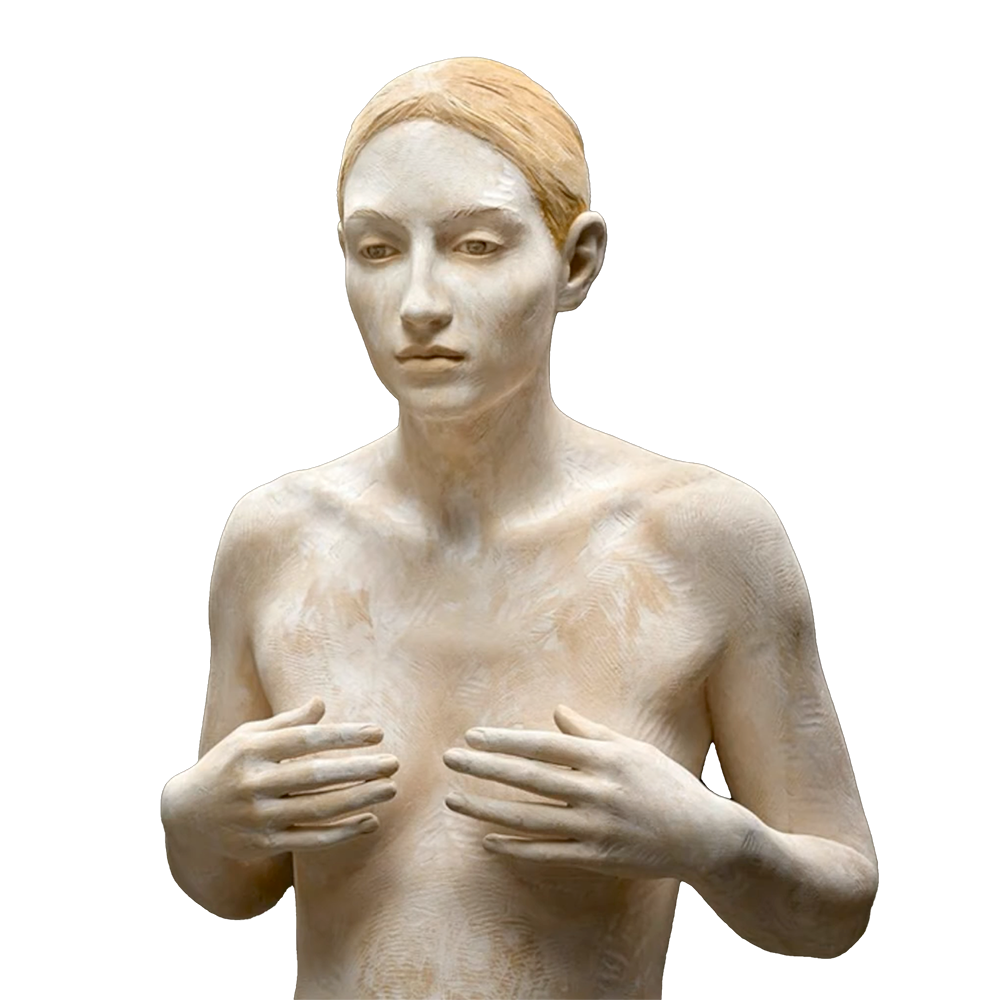

Bruno Walpoth honors the vulnerable human, like a naked woman defensively holding her hands in front of her breasts.

Bruno Walpoth was born in 1959 in Bressanone (Brixen) and grew up in a family of wood carvers. As a child he already came to the studios of his grandfather and his uncle — both master craftsmen in religious sculpture.

A contemporary signature

In 1973 Walpoth began his first formal training with the local master wood carver Vincenzo Mussner in Ortisei. He worked with him intensively for five years on his basic technical skills. He then continued his education at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where he studied from 1978 to 1984 under Professor Hans Ladner. During this period he broadened his sculptural language and developed his own — and contemporary — signature. First abstract, then returning to the figurative.

This combination of traditional master-apprentice training in Val Gardena and academic art education is characteristic of his work — and that of his contemporaries from South Tyrol. The craftsmanship discipline of wood carving forms the foundation, but the conceptual horizon is entirely today’s. The figurative model is not abandoned, but transferred to the world and thinking of the 21st century.

As tall as a real person

Walpoth mainly makes life-sized figures from tree trunks (especially linden). What is special is that he works on a 1:1 scale. His sculptures are as tall as the viewers. They stand eye to eye with each other — when the sculptures are not lying down.

It is not the only difference. Unlike Walpoth’s sculptures, visitors to an exhibition are extroverted, outward-looking. They want to look around, absorb everything. Walpoth’s figures, on the other hand, pose — often rigid and still — with a gaze that does not even directly meet the viewer. The sculpture is somewhere else with its (or her) thoughts, clearly turned inward. Sometimes even huddled defensively, like a fetus in an adult’s body.

It is not a classical pose, where existing sculptures could serve as examples. Walpoth therefore invites models to his studio, who pose naked for him. Even his own son posed as a model for a sculpture. Walpoth observes their expressions carefully before he carves.

Bruno Walpoth works with a rasp on a male nude, again in a vulnerable pose reminiscent of a fetus.

That atmosphere of silence and inner reflection is deliberately chosen. Walpoth does not want to lead the viewer to a story, but to invite contemplation. The body of his sculptures is not a medium for action, but an independent carrier of feeling and presence.

Although he comes from a traditional environment, Walpoth works the wood in his own way. Before the sculpture is finished, he paints the wood with white primer — I think water-based. He then rasps and carves further, emphasizing the texture, grain and form of the wood.

Unlike in earlier times, when paint ‘hid’ the wood of religious statues, Walpoth knows how to actually enhance the material sensuality of his vulnerable men and women this way. The wood gets its own story: his vulnerable people seem only half present, as if they are in an ‘in-between space’. That is a very different feeling from what some critics note, who characterize his figures as ‘melancholic’.

Scars on the skin

I am very charmed by the scars that a rasp leaves on the skin. It’s not obvious: such a series of parallel scratches on an arm, or even on the face. The effect is less emphatic than tattoos, but more material. I must confess that I have unconsciously adopted part of his working method, which I saw years ago in videos on YouTube. What apparently touched me so much about Walpoth is the way a simple scratch of the rasp can evoke emotions — a nuance you only feel when you really look at it.

Bruno Walpoth applies a layer of white primer to the sculpture, before finishing further.

I prefer a roughly planed surface to perfectly smooth-sanded wood. I also prefer a colorless parquet varnish, which makes the sculpture somewhat whiter, to an oil that colors the wood deeper and darker in tone. Especially on linden wood, which has little character and grain of its own, this is a find. Now that I watch these videos again, I should thank Walpoth for the inspiration for my own search.

Jan Bom, January 17, 2026