Max Ernst rubbed wood grain onto paper, a technique he called frottage. With graphite, chalk or charcoal he scratched over paper that lay on rough floorboards or tree trunks. He used the drawing of the wood grain as a starting point for creating surrealist images and landscapes.

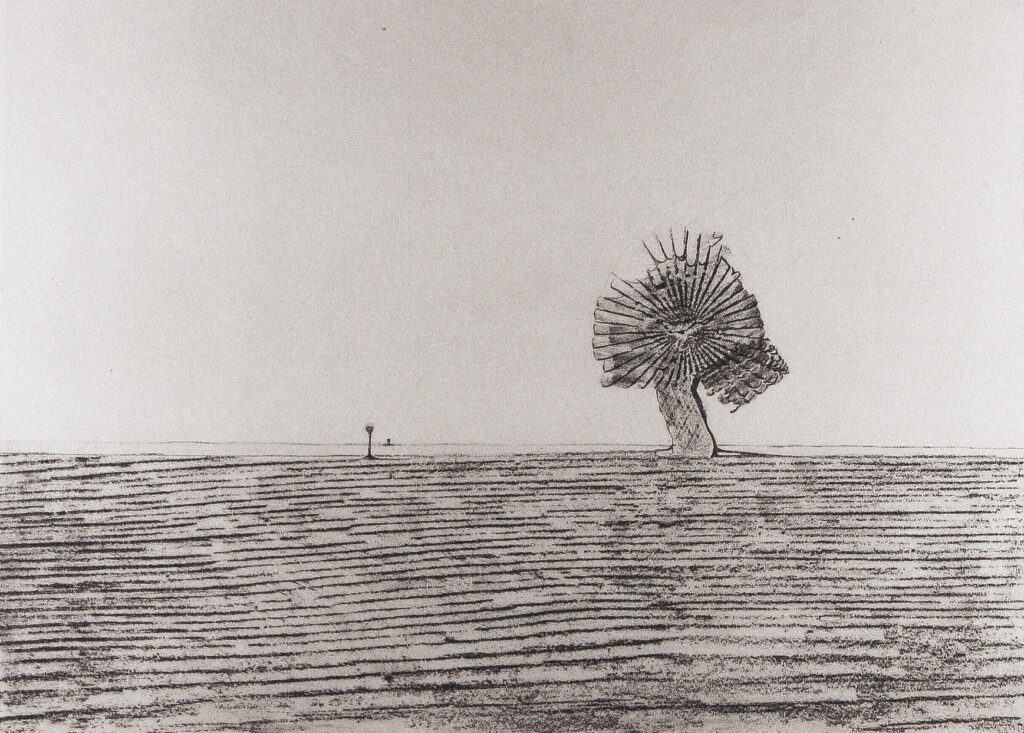

Max Ernst rubbed wood grain onto paper and saw in it a grassland landscape in South America, Les Pampas.

Max Ernst (1891-1976) is certainly not a wood carver, but the drawing of wood did inspire him to make groundbreaking art. He saw this way of working as a way to reveal the subconscious. It is for this reason that I find Ernst interesting for this website and certainly also as a reference to Dendroism. Also much earlier, for other surrealists like Jean Arp, Ernst was a source of inspiration.

The discovery of frottage (the French word for rubbing) in 1925 marks a turning point in Max Ernst’s oeuvre. During a stay at an inn by the sea he became fascinated by the worn wooden floor. The grains, scratches and irregularities formed an inexhaustible source of images. By placing the paper directly on the wood and rubbing over it, Ernst captured this history of use.

Subconscious visible

This attitude closely aligns with the principles of Surrealism, in which chance, the subconscious and the dream world play a central role. Yet Ernst’s method is special: he does not invent the images, he ‘discovers’ them. The wood grain is not a background, but an active co-player. In that sense the wood is no longer a material, but a visual memory bank in which landscapes, creatures and structures lie hidden.

Within the principles of Dendroism — in which the form of the tree or the drawing of the wood forms the basis for the artwork — Max Ernst is an early source of inspiration. He does not work with wood as sculptural material, but with wood as origin of image. The grains, knots and growth directions are read as if they were fossils of images. What Ernst does is look until the wood looks back.

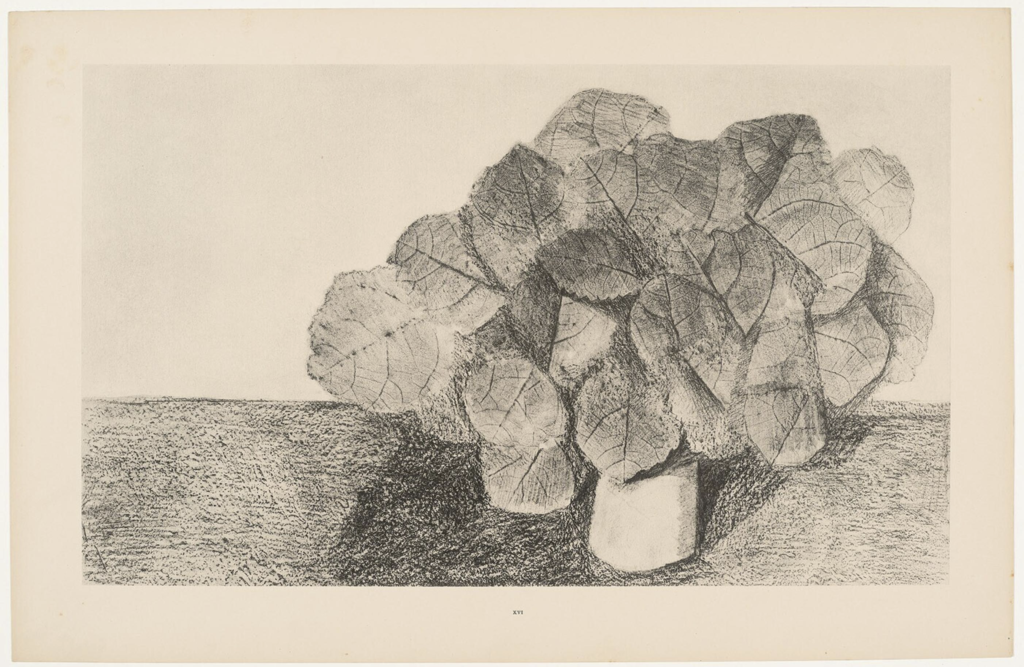

Max Ernst rubbed wood grain onto paper, but also leaves and shells.

In works from the portfolio Histoire naturelle (1925–1926, edition of 300), also in the possession of museum Boijmans van Beuningen, this principle is consistently applied. Forests transform into architecture, tree structures become landscapes, grains become feathers, scales or skin. They are no longer illustrations of trees, but images that emerge from the wood. Thus the role of the artist shifts: not the maker, but the receiver and translator takes center stage.

From frottage to grattage

The frottage was not limited to drawings. Ernst translated the found structures into paintings via grattage, whereby he scraped paint over a textured surface. Ernst placed a canvas over a texture, scraped the surface, and let the underlying structures — sometimes also of wood — appear as a starting point for his imagination. Thus his famous forest landscapes and cities from the thirties arose, in which tree-like forms rise up as living architecture. These forests are not idyllic nature images, but dense, sometimes threatening spaces, in which growth and rigidity coincide.

Here too wood remains — albeit indirectly — present as a formative principle. The paintings are constructed like condensed wood structures: layers, grains, vertical tensions.

Chess, one of the few works executed in wood itself by Max Ernst.

Although Max Ernst is best known as a painter and graphic artist, he also made sculptures and objects. But rarely are these executed in wood; usually he worked in plaster and bronze. Yet these sculptures also bear a clear kinship with natural, often tree-like forms. His totem-like figures, hybrids of human, animal and plant, seem to have grown rather than been made.

The large chess set that Ernst designed in the forties, he did make from wood. The pieces are archetypal, almost ritual in nature. They refer more to mythical figures than to classical chess pieces like Queen or Rook. However famous, these chess pieces do not appeal to me very much. The story of the wood itself has disappeared.

Wood as co-creator

Max Ernst taught artists to look differently: not at what they wanted to make, but at what the material itself already contained. In that sense his frottage is not just a technique, but an attitude. An attitude that takes the wood seriously as a co-creator. Precisely there his work touches the core of Dendroism.

Jan Bom, January 14, 2026