Louise Nevelson made monuments from found wood: assemblages of crates, chair legs, turned spindles, columns and door panels. She assembled all the loose parts into architectural installations and painted them matte black. The Centre Pompidou in Metz (France) shows her ‘monuments’ this year (2026).

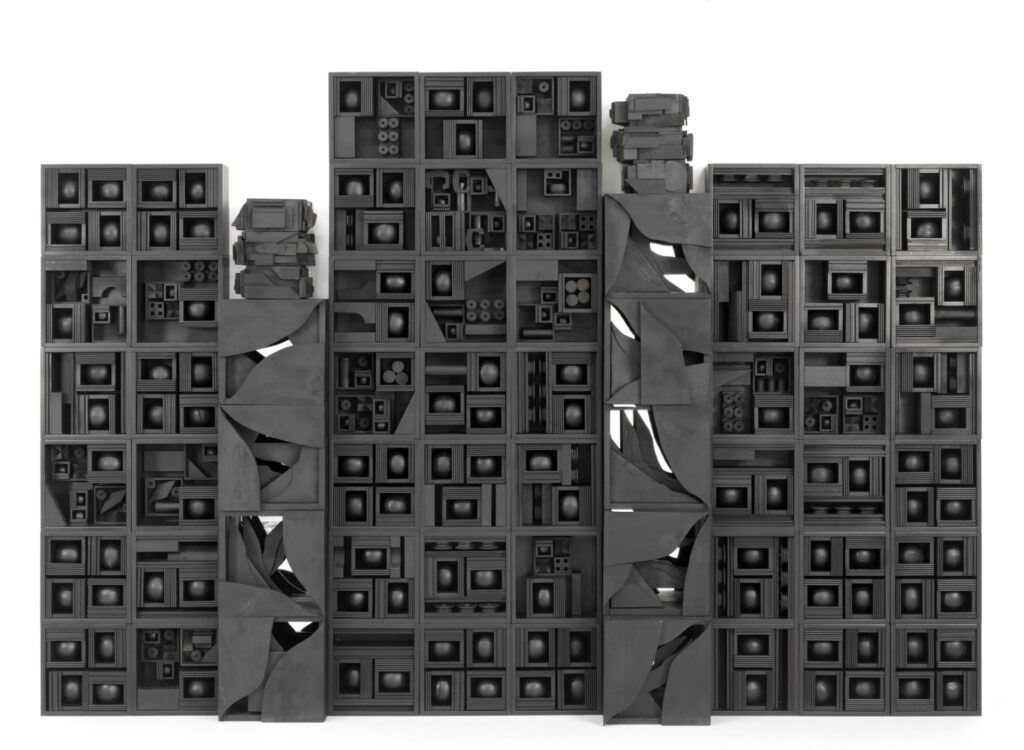

Rain Forest Wall (1967), in the possession of museum Boymans van Beuningen in Rotterdam.

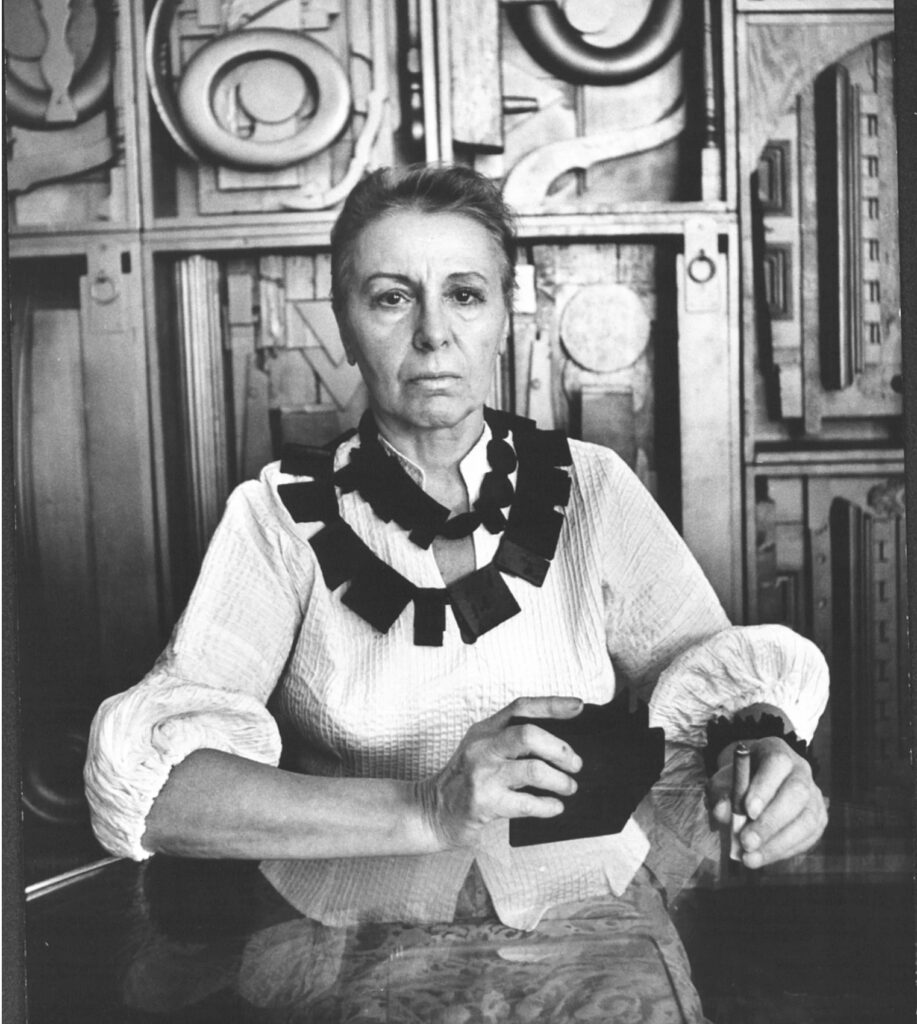

Louise Nevelson (1899–1988) belongs to the most influential sculptors of the twentieth century. In her wooden worlds Nevelson transformed discarded wood into sculptural installations. Her oeuvre shows how material, memory and space merge into a unique visual language. Abstract yet very mystical and personal.

Born in present-day Ukraine

Nevelson was born in the last century as Leah Berliawsky in Pereiaslav, in present-day Ukraine, near Kyiv. In 1905 her family emigrated to the United States and settled in Rockland, Maine. The rugged nature and wooden houses of New England formed an early visual environment. Later all this wood would unconsciously resonate in her work. Wood was everywhere here: in the forests, as building material, as utensil. In short: as carrier of traces of life.

From an early age Nevelson felt attracted to art, but her path to becoming an artist was not self-evident.

After a failed marriage and the birth of her son, Nevelson moved to New York in the twenties. She was determined to become an artist. She studied at the Art Students League and also briefly worked as an assistant to Diego Rivera (Frida Kahlo’s husband), from whom she learned the importance of scale, rhythm and architectural coherence.

Yet it took decades before she found her own, recognizable voice. Only in the fifties did Nevelson begin working intensively with found wood — a choice that was both practical and conceptual. She lived in poverty and used what this world city offered her: discarded objects, construction waste, discarded household goods. But this limitation grew into an aesthetic and philosophical starting point.

The found wood did not function for Nevelson as neutral material, but as carrier of a past. Each fragment had already had its own life. It had been touched, used, worn. By collecting and arranging these elements, she appropriated their history. She recreated the demolition wood into a new whole.

Rhythmic structure like music

Her assemblages consist of wooden boxes and compartments, in which objects are carefully placed. The repetition of shapes — circles, squares, vertical and horizontal lines — give her installations a rhythmic structure reminiscent of music or poetry. Nevelson took modern dance lessons for twenty years and was a great fan of ballet pioneer Martha Graham. She was also good friends with composer John Cage. He called her work ‘music theatre’.

A crucial aspect of Nevelson’s work is her use of matte monochrome colors, especially black, white and gold. The black, which she often described as ‘the most aristocratic color’, unites the disparate parts into one visual unity. By painting everything in a single color, individual details do not disappear, but become subordinate to the whole. The wood loses its literal identity and becomes sculptural matter. At the same time, the texture remains visible: grains, breaks and wear betray the past of the material.

The installation Sky Cathedral, as it stands in the MoMA in New York.

Nevelson herself preferred to speak of her works as ‘environments’ rather than as sculptures. The word ‘installation’ has only existed since 1959. A work like Sky Cathedral (1958) consists of a wall of wood that surrounds and engulfs the viewer. The scale is human and superhuman at the same time: you stand opposite the work, but you ‘are also in it’. She herself said about her work, in 1964: “I myself need, for my place of consciousness, a form. It’s almost like you are an architect that’s building through shadow and light and dark.”

This spatial experience is essential to her work. The wood becomes architecture. Call them monuments in the form of a kind of inner city or temple. Art historians have often pointed to spiritual influences in her work, ranging from Jewish mysticism to Gothic cathedrals and pre-Columbian architecture.

As a woman in a male-dominated art world, Nevelson had to fight hard for recognition. For a long time her work was seen as ‘decorative’ or ‘crafty’. That happens to more artists who choose wood. It was a material that did not fit within the art movements of modernism where steel and stone and oil paint dominated.

Even painted white, Nevelson chose only a single color: as with this work ‘Dawn’s Presence, Two Columns’.

Yet she held on to her vision. Her public persona, with dramatic clothing, artificial eyelashes and jewelry, was deliberately constructed. Nevelson made herself into a living artwork. This mythologization of her own person went hand in hand with her sculptural universe.

In the sixties and seventies Nevelson’s international reputation grew. She represented the United States at the Venice Biennale and received major public commissions. Yet found wood remained the core of her work. Even when she worked in metal, the logic of assemblage and modularity remained leading. Her wooden installations continued to testify to a fundamental conviction: that art arises through the ordering of chaos, through finding coherence in fragments.

Echoes of human use

Louise Nevelson died in 1988 in her city New York, her stage. Her art has had lasting influence on later generations of artists, especially within assemblage art, installation art and working with found materials.

In this time when sustainability and reuse are becoming increasingly urgent, her approach to discarded wood gains new relevance. Nevelson did not yet know the word ‘circularity’, let alone ‘upgrading waste’. Yet she showed that what is thrown away is far from dead. It is only waiting for a new order, for a new meaning.

Her installations of found wood are not silent objects, but living structures full of echoes of human use and memory. They form monuments without heroic figures, cathedrals without religion, cities without floor plan. In the work of Louise Nevelson the wood speaks — silently, painted matte monochrome, but laden with time. Precisely therein lies its lasting power.

The retrospective exhibition ‘Mrs. N’s Palace’ begins on January 24 and will run until August 26, 2026 at Centre Pompidou in Metz, east of Paris. Louise Nevelson made monuments from found wood and here they can be found.

Jan Bom, January 5, 2026