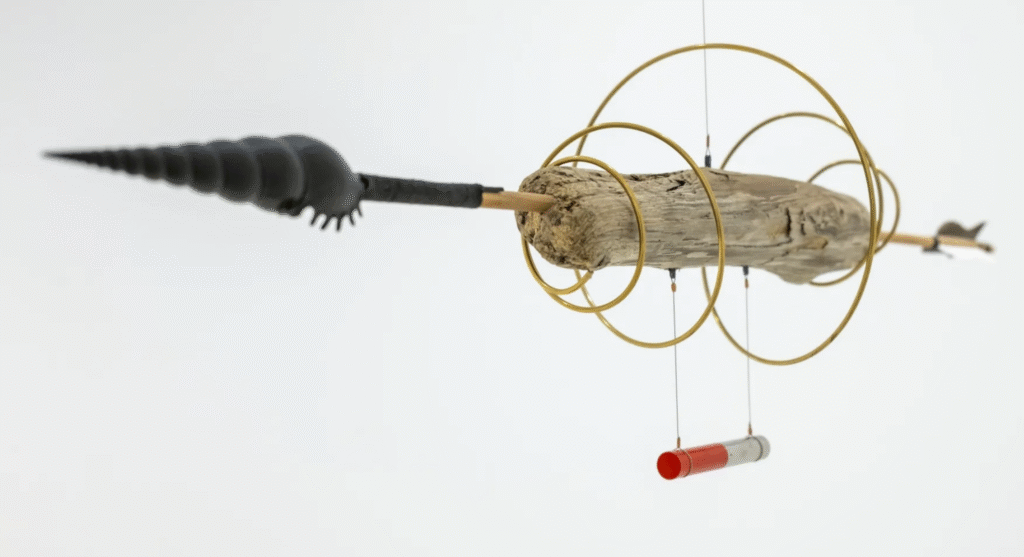

Olafur Eliasson made a compass from driftwood, washed ashore on a beach in Iceland. He called his artwork Climate Justice Navigator.

The Climate Justice Navigator (2018), a real compass made of driftwood.

Since the nineties, Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson (1967) has conquered a special position in the international art world. With his Studio Olafur Eliasson in Berlin he built an interdisciplinary laboratory in which art, science, craft and activism intersect.

His oeuvre is considered sensory and poetic. At the same time it is morally charged: it does not only want to show beauty, but to change the perception of the viewer. Eliasson repeatedly tries to reshape the relationship of the audience to the world.

His most recent work of driftwood, Compass travellers (2022).

Within this mission the group of works made from washed-up wood — such as the project Driftwood, the monumental Compass travellers but especially the sculpture Climate Justice Navigator — occupies a special place. These sculptures embody the core idea in Eliasson’s thinking: human orientation can never be seen separately from ecological processes.

The spectacular Northern Lights

Eliasson grew up between Denmark and Iceland, in an environment where nature was not a background décor, but an active force. The experience of glaciers, volcanoes, fog banks and the spectacular Northern Lights nourished his early awareness of the world as a constantly changing, unpredictable environment.

During family vacations he regularly saw washed-up wood lying on the Icelandic coasts — driftwood that turned out to come from Siberian forests. It had drifted on ocean currents. In that driftwood lies the core of his thinking about art. Natural materials are not dead, static objects. They testify to movement, flow, time and change.

That thought forms the core of Driftwood, an ongoing research and art project in which his studio collects and transforms washed-up wood. The wood bears traces of geological zones, of salt, wind and erosion. By reusing this material, Eliasson makes tangible how everything is connected — how even a piece of wood that washes up on a coastline is part of a much larger whole.

The back of the sculpture Climate Justice Navigator, with a working compass hanging below.

In the sculptures Driftwood, Compass travellers and Climate Justice Navigator this idea is expressed. The washed-up wood symbolizes natural processes. The painted compass invites the viewer to find their own direction in a world that is no longer clearly defined. The works emphasize that art is not only something to look at, but something to think and move with. Eliasson wants to demonstrate that orientation is not only a matter of geographical position, but of inner attitude, ecological responsibility and relational connectedness. And thus is not just about passively looking at art, but becomes an experience.

A truly functioning compass

What makes the sculptures like Climate Justice Navigator extra special is that they are not only a symbolic, but also a truly functioning compass. Eliasson integrated a precisely balanced construction into the work. Magnetic elements and a sensitive suspension system ensure that the central arrow continuously orients itself towards magnetic north. This keeps the compass in motion. This can be very subtle, due to an air current as visitors walk by. The sculpture responds to the world just as we should in thinking about climate justice, Eliasson believes. Take some responsibility, he wants to say. Also for global inequality.

Olafur Eliasson partially painted four driftwood tree trunks.

His most recent work with washed-up tree trunks dates from 2024: ‘More than Human Gathering’. Studio Olafur Eliasson painted four driftwood trunks by hand, creating a flowing transition from one end of the trunk to the other. There is a contrast between the attention with which the tree trunks have been treated and the deliberate nonchalance with which they are exhibited. They lean against the museum wall as if they have been put down there rather than exhibited. As if they are resting for a moment before continuing their long journey again, across the oceans.

Jan Bom, November 25, 2025 (photos Jens Ziehe and Nieuwe Instituut)