Auguste Forestier was as a psychiatric patient the most important inspiration for Art Brut. His wooden sculptures of generals, human-animals, ships and houses are now in museums and still travel the world. Thus Forestier’s dream of making distant journeys finally became reality.

Auguste Forestier, inspiration for Art Brut, also made generals that he sold as children’s toys.

Call it Art Brut, Outsider Art, naive art or folk art. The fact is that the French artist Jean Dubuffet (1901 – 1985) visited the psychiatric hospital in Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole in the 1940s. He had seen wooden works by patient Forestier and wanted to meet him. Dubuffet believed that people who had not been touched by conventional art training were not restrained by a superego. The absence of academic knowledge would even enable them to better express primal drives and desires, emotions that were directly connected to mystical forces and the universe.

There in the institution, to his amazement, many more patient-artists turned out to live who drew, worked with textiles, wrote and painted. There were even so many that Dubuffet coined the naive art movement ‘Art Brut’, to indicate how the patients made their imagination tangible.

None of them were hindered by any knowledge of art history. They stood far outside society. Locked up in an institution. The director did give them all materials to paint, embroider, dance or work in wood. But the most famous of all became Auguste Forestier.

A house by Auguste Forestier especially showed a gate to freedom.

Auguste Forestier (Naussac, 1887-Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole, 1958) started running away from home as a boy, without a penny in his pocket. He boarded trains without buying a ticket and undertook long journeys. It must have been a longing for unknown lands that explains all his escapades. But every time he was brought back to his village by the police.

The fascination with trains remained. Forestier even caused a derailment in a tunnel in May 1914 by placing stones on the tracks. At his arrest he stated: ‘I wanted to see how the stones were crushed. I didn’t think the train would derail’.

Sculptures from bones from the butcher

In prison he carved wooden medals, which he said had been given to him by the railway company as a token of appreciation. Forestier was ultimately not convicted for destroying public property, but was considered irresponsible for his actions. He was locked up in what was then still called an ‘asylum’ or even ‘madhouse’, in Saint-Alban in the department of Lozère, not far from the Spanish border and the Mediterranean Sea.

In 1915, one year after his psychiatric confinement, it is reported that he ‘is often busy drawing and carving bones from the butcher. He works very hard and achieves a kind of primitive artistry’.

Forestier’s wanderlust had not yet completely subsided: he was considered ‘an escape risk’. In total he ran away five times between 1914 and 1923. Yet he began to replace his physical journeys more and more with journeys in his imagination. His drawings and sculptures took him on fictitious journeys through history. The psychiatrist Jean Oury, who worked at Saint-Alban from 1947 to 1949 and treated Forestier, diagnosed that Forestier’s work ‘would always carry the traces of the ideal of the traveler’.

Auguste Forestier imagined an imaginary past with non-existent military leaders.

Forestier’s fantasy world was certainly enriched by the place where he lived. The institution was housed in an old 13th-century castle that was extended with four towers in the 16th century. The outer walls are massive; only the main entrance and the window above it were decorated with pilasters and pointed gables in pink sandstone. Forestier was also not indifferent to this door; it symbolized both his confinement and an opening to the world. He placed his sculptures at this gate to exchange them with hospital staff. He also sold them to passing farmers, who bought the figurines as toys for their children.

His own workshop in the corridor

Forestier had even created a kind of workshop in the corridor leading from the scullery to a courtyard. He had placed a workbench there, and possessed some rudimentary tools, a small chisel, a knife and nails. He wandered through the hospital to collect broken objects and discarded scraps of fabric. Animal teeth, everything he could use. He also began to carve arms, legs, heads, wings and decorative moldings from the pieces of wood he had collected.

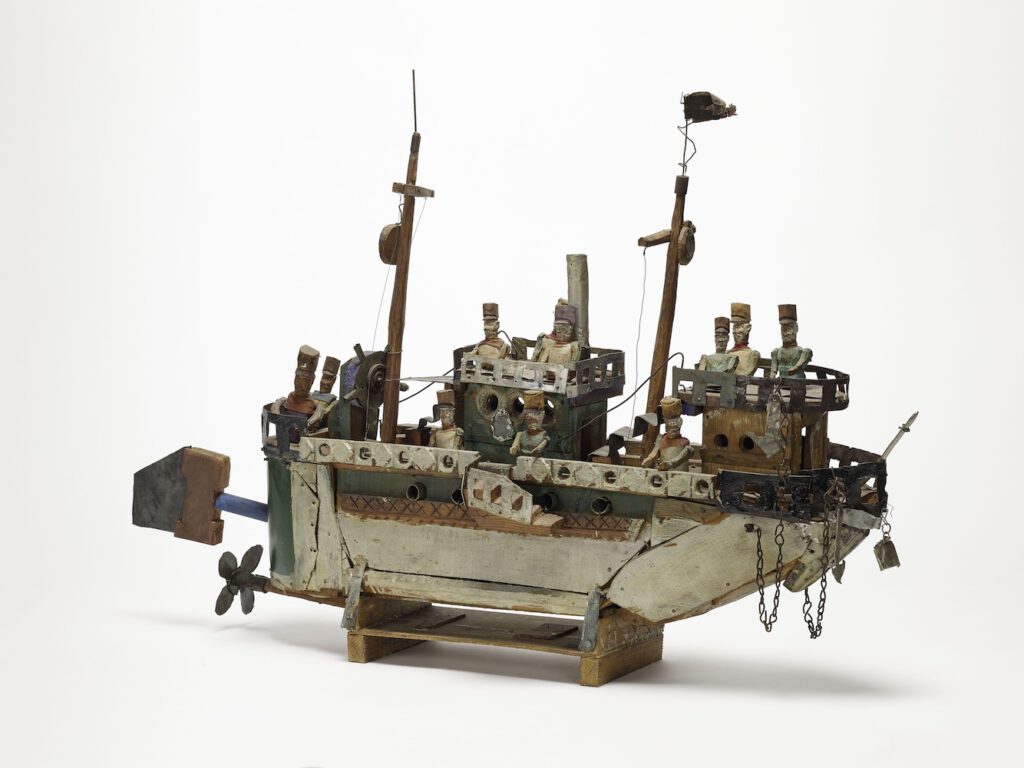

Forestier achieved such technical skill and speed in doing so that he could produce a rich range of objects. He constructed his figures, soldiers, boats, horsemen, animals, houses, children’s furniture and carts in such a unique way that a personal ‘signature’ emerged.

A monster by Forestier with real teeth, feet and the tail of a fish.

The metamorphosis of man and animal became an important theme for him. Perhaps a local legend inspired him, about the ‘terrible beast of Gévaudan’, a kind of werewolf. This terrorized the villagers centuries earlier and would have made many victims.

The monsters that Forestier constructed evoke images of what this beast might have looked like: his animal figures sometimes have the snouts of wolves, the tails of fish, but also contain parts of birds – wings grow from the backs of several of them. But they are also partly human, because they stand on two feet. They can fly, swim and walk. Dressed in clothing made from remnants of fabric and decorated with medals, some monsters have a human head and body, but with a bird’s beak.

An enlightened psychiatrist

Because he eventually no longer dared, or wanted, to go outside the walls of the hospital, Forestier also invented the ‘stationary traveler’. Although he had never seen the sea, he began to build fantasy ships. He let them ‘sail’ on the roads of Lozère by selling and trading them. One such ship produced a special photograph, because the new free-spirited director of the institution climbed onto the roof with it and let it sail imaginarily through the air.

The enlightened director of the institution, Francesc Tosquelles, lets a ship by Forestier sail through the air.

The role of this psychiatrist Francesc Tosquelles was of enormous significance for Forestier’s development. The Spaniard had fled from the Spain of dictator Franco. In the middle of World War II, in 1943, he took over the leadership of Saint-Alban with all his ideals.

The institution was in an institutional crisis at that time. Under the yoke of the French Vichy government and the occupation by the Nazis, basic provisions for the psychiatric population of the country were almost completely abolished. The hospital at that time had just over 850 patients.

Space for dancing and theater

Tosquelles radically transformed the organization by implementing his groundbreaking ideas about ‘institutional psychotherapy’ there. It is an approach to psychiatric care that wants to eliminate the hierarchy in the organization. He thus tried to break down the boundaries between patients, doctors and facility staff.

Embedded in Tosquelles’ approach to psychiatric treatment was including patients in the daily activities of the hospital. And that was a rich palette: from maintaining the facility and a space for parties, patients could also organize plays and dances. They were also given access to a library, cinema and art workshops.

The director was also open to making contacts with the local community and other outsiders. Due to the war situation, dissidents took refuge in the institution to avoid persecution. Among the outsiders who spent time at Saint-Alban was also the French artist Dubuffet, who could not believe his eyes when he saw the creative results of the new regime. They were so comprehensive that he invented the term ‘Art Brut’ for all those artist-patients. He took works by Forestier to Paris to show them to Picasso – among others.

Not psychopathological art

According to senior curator of self-taught art and Art Brut, Valérie Rousseau, working at the American Folk Art Museum in New York, Dubuffet and Tosquelles did not immediately click: ‘As a medical practitioner, Tosquelles initially greeted Dubuffet’s collecting initiatives with skepticism. He saw him as an aesthete looking to market works that came from the psychiatric treatment of patients. The aim of institutional psychotherapy at Saint-Alban was not that, but tried to rehabilitate patients by bringing them to social exchange through various forms of labor.’

Rousseau: ‘Tosquelles had no interest in Dubuffet’s cultural mission with his Art Brut. Meanwhile, Dubuffet opposed the isolation of individuals based on a separation between normal and deviant behavior, a separation he found false.’

Yet the two eventually found a workable basis that changed art history. Or at least enriched it. With self-taught artist-patients and many other untrained makers.

Those who want to see works by Forestier can visit the Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut, Villeneuve d’Ascq, among others. Other museums: Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Musée de la Création Franche in Bègles, France and the Musée de l’Art Brut & Singulier in Montpellier, France.

Text Jan Bom