Brancusi: The Endless Column. In Romania stands this recognized ‘world monument’ of iron and bronze, no less than 30 meters high. It seems to almost disappear into the clouds. But the Romanian artist Constantin Brancusi (1876 – 1957) carved the original idea much earlier, in 1918, in oak wood. With the same repeating form, the sculpture represents the idea of ‘endlessness’.

The Art Bible Janson’s does not devote a word to this monumental work. Neither to the original wooden one, nor to the gigantic metal version. However, Brancusi’s vision is captured in a beautiful quote: ‘Simplicity is not an endpoint in art, but you arrive at simplicity despite yourself when you penetrate to the real meaning of things’.

Father of Modernism

Brancusi is counted among ‘the fathers of modernism’ in art, just like his contemporaries Picasso and Duchamp; they broke with the figurative tradition. It is fascinating to see how Brancusi made a woman’s head increasingly abstract and reduced it to a few round shapes, the hair bun on the back of the head to a square. Or a pair of circles.

‘Tête’, an abstracted head from the beginning of Brancusi’s career.

This wooden representation of a head according to Brancusi really needs the title ‘Head’ (‘Tête’) to be able to see a head in it. Is it a loudly screaming child? A baby in a cradle? Brancusi was inspired by Romanian folk art and African masks, although he later denied the latter. Strange, because another wooden sculpture of his of a crouching woman has clearly African characteristics. This head from 1919-1923 is in the possession of Tate Modern in London.

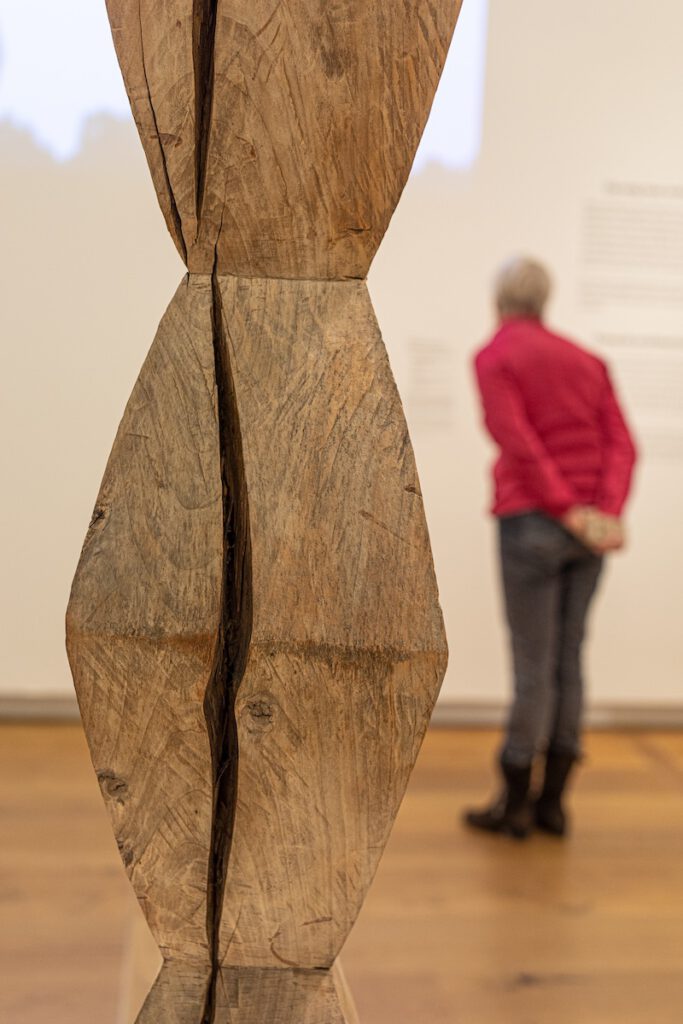

The ‘Endless Column’, photographed in the H’ART Museum in Amsterdam, with beautiful shrinkage cracks.

The original version of the ‘Endless Column‘ can be found in the MoMA in New York. In 2025, one of the other wooden versions of this ‘column’ also temporarily stood in H’ART Museum in Amsterdam, in a magnificent exhibition with many other wooden sculptures by Brancusi. This oak version of the column has enormous shrinkage cracks, which certainly contribute to the dramatic effect of the sculpture.

Torso of a Young Man, walnut wood (1923)

Remarkable is also that Brancusi made wooden busts where it is not clear whether it should be a man or woman. With some sculptures it can even be both. The title explains Brancusi’s final gender choice, as with the sculpture ‘Torse de Jeune Homme’. In translation: ‘Torso of a Young Man’, from 1923.

A phallic symbol without genitals

Male sexual characteristics are however completely absent, unless it is the totality of the sculpture, which can be seen as a phallic symbol. In that case, it is a special example of ‘pars pro toto’; a figure of speech where one names a part of an object when one means the whole object.

‘La Tortue’, made during the war years in Paris.

Imagination is also needed for Brancusi’s wooden sculpture of a turtle. Here too he stays close to the original shape of a horse chestnut trunk. He mainly sanded the part of the shell smooth to an oval shape, almost a heart. ‘La Tortue’, from 1941-1943 received a beautiful message from the artist. ‘It is the art of the artist to bring out the life from the material itself, not to impose his will on it’. Beautiful is the contrast of the polished wood on the rough oak pedestal, where the traces of the wide gouge are still clearly visible.

Brancusi made all his pedestals himself, with a strong preference for rough oak wood. Perhaps that is how the idea for the ‘Endless Column’ came about, an endless pedestal that rises ‘into the heavens’.

Jan Bom, last edited November 12, 2025