Janson’s art bible fails, even though it is a holy book for the art world. What wood carving art is in it? Or better: what and who are all missing? A lot, unfortunately. In the 1184 pages, only 25 illustrations of wooden art objects can be seen.

Janson’s History of Art describes the development of Western art from prehistory to the present. In about 25 illustrations, wood as a material is central. That is a very meager harvest, because Janson’s is a huge book of 1184 pages. The last and eighth edition of this sixty-year-old Art Bible even weighs 4.5 kilos. It’s expensive too. Fortunately, Janson’s can be consulted on the internet. Free.

Even though it is so thick, it is a worthless book for those interested in wood carving art. Missing are both old and modern artists. Nothing about all those wooden artworks from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance, when Western churches were richly decorated with wooden representations. It was precisely during those centuries that the skill of wood carvers and furniture makers reached a peak. Just go and look at hall 1 of the Rijksmuseum. That aspect is almost entirely missing from the illustrations in the latest update of Janson’s. Only the high church ceilings of carved wood are shown. Too high and too far away to see details.

This creates an unbalanced picture, because most of the shown illustrations with wooden art objects in Janson’s are from after 1900. It is also very remarkable that the wooden expressions of the Dadaists receive so much attention. But the editors of Janson’s like woodcuts the most. Only their development over the centuries is well described. For the rest, only one conclusion is possible. Janson’s art bible fails.

Below we show the illustrations of wood-related art objects from the latest edition of Janson’s.

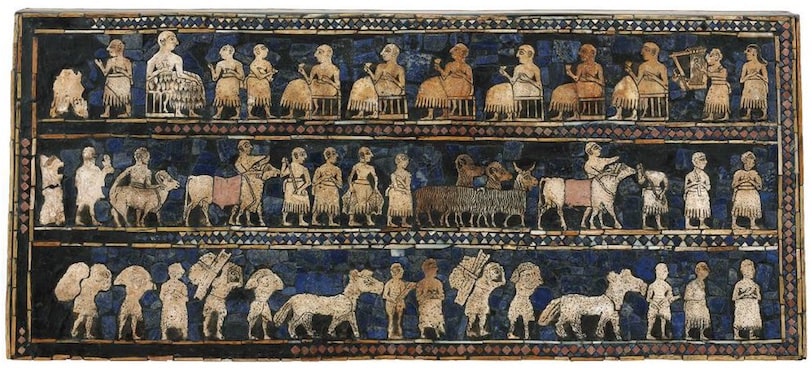

From the burial chambers of Ur – Muqaiyir in present-day Iraq – comes a figurine of a standing goat. A ram, to be precise. It is the very first wooden object in Janson’s, dated: 2,600 BC. At 50 centimeters high, the wood is covered with gold and the blue gemstone lapis lazuli. Archaeologists led by Leonard Woolley found it in the 1920s at the Royal Cemetery (‘The Great Death Pit’), under the walls of the city of the Biblical figure King Nebuchadnezzar. Besides the ram eating on its hind legs, 1,840 other historical objects were found, including objects used for offerings. A wood relief of 20 centimeters height shows a military victory, a feast, animals and shepherds. These are the very first wooden objects, found on pages 26, 27 and 28 of Janson’s. The Art Bible skips much older preserved wooden cultural expressions, such as the ‘Shigir Idol’ from Russia, which must be about 11,600 years old.

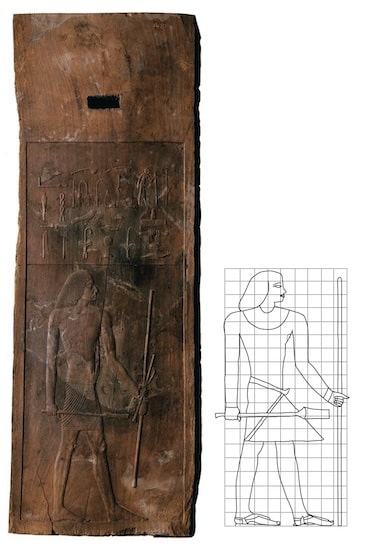

On to ancient Egypt, also a cradle of our civilization. From 2660 BC comes this wooden panel, also a relief, representing Hesy-ra from Saqqara. It is 114 centimeters high and is an example of the frontal representation method of the ancient Egyptians. Only the side of the head is shown, with only one eye. The shoulders are perpendicular to the head, which is not realistic. The same goes for the two left feet. The figure is a high-ranking official, found on page 60 in the chapter on the Ancient World.

A first wooden bust also comes from Egypt, approximately 1353 BC. It is a bust of Queen Tiy, carved from yew. The sculpture is richly decorated with inlaid ebony, alabaster, gold, silver and again with the blue gemstone lapis lazuli, which today is mainly mined in Afghanistan. The head is small, no more than 9.4 centimeters high. Queen Tiy is the mother of the much better known King Akhenaten. Found on page 74.

The first European wooden art object that we find on page 322 in Janson’s is a wooden ‘burial ship’ of Norse Vikings. We are then already in the year 834 AD. The prehistoric cave painters from France have already passed, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Etruscans and the Romans. Nothing remains of the first wooden statues or constructions for buildings from ancient Greece. The wooden horse of Troy has also been lost, just like the wooden cross on which Jesus was crucified. It can only be described in the text. Janson’s shows us, besides the Viking ship, also the head of a gruesome sea monster, 12.5 centimeters high. It was part of the ship with which a deceased Norse Viking princess was sailed out to sea.

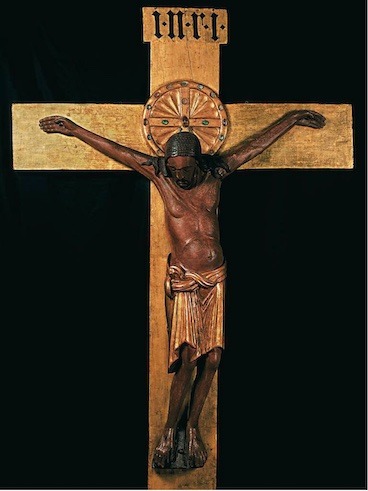

A sculpture of Christ on the cross follows on page 343: the Gero Crucifix from (approximately) the year 970, which still hangs in Cologne Cathedral. It is a life-sized sculpture with a ‘monumental presence’. It is the first time that wood carvers depicted Jesus on the cross. Carved in oak wood, the leaning forward body of Christ is particularly striking. The viewer almost feels the physical pain on the arms and shoulders. All life has already drained from Jesus’s face.

The ‘Holy Virgin of Essen’ on page 344 was also once made of wood, but that has now completely decayed due to moisture and possibly wood rot or woodworms. Because the sculpture was gilded, only the shape, the golden casing, remains. And the staring eyes, made of semi-precious stones. Janson’s characterizes the sculpture as a fine example of a new aesthetic that would dominate in Western Europe in the eleventh century.

The foundations of Westminster Hall in London date from 1097, built in the ‘Norman Romanesque’ style. But the magnificent current roof is younger and was added to this church between 1395 and 1396 by Henry Nevele and his master carpenter Hugh Herland. He managed to span a width of almost 20.5 meters without the support of pillars. That was unique for the time, because the roof weighs no less than 660 tons. The beams are decorated with carved wooden flying angels and heraldic boards. Janson’s shows the roof on page 429.

On page 434 follows a wooden pietà, a representation in which Mary this time holds not the ‘baby’ Jesus, but her son who died on the cross in her arms: the Roettgen Pietà. We are then already in the fourteenth century, the Gothic period. It is a realistically carved sculpture, painted and intended to be placed on the altar, 87.5 centimeters high. Believers thus clearly received the message: suffer with Mary, her pain is unbearable. Christ’s wounds are grotesque, like bullet holes, highlighted with red paint.

The Dutch sculptor Claus Sluter is not skipped in Janson’s. His wooden sculpture of Christ on the cross, which the Rijksmuseum is so proud of, is skipped. The standard work only discusses Sluter’s works in stone, particularly the Well of Moses (1395-1406), which can be found at the Chartreuse de Champmol in France. We are still in the Gothic period. The beautiful altarpiece by Melchior Broederlam in the same church, which Janson’s also shows, is of course painted on wooden panels.

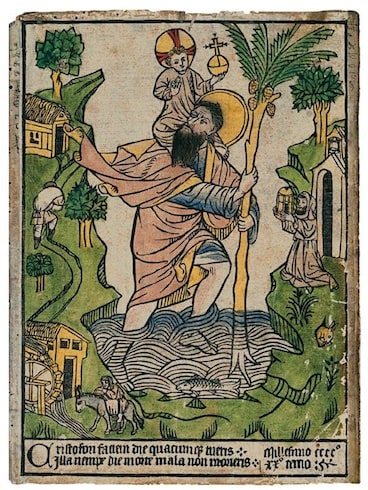

The roots of the printing art lie in the Middle East, about 5,000 years ago. The Sumerians were the very first ‘printers’ who made impressions with images in stone in clay; illustrations but also texts. Only after this idea traveled via India to China did ink come to make prints on silk and wood. It stimulated the Chinese to find another carrier for their ‘prints’: thus the invention of paper came about. The return journey to the West took thousands of years, but once accepted here too, it went quickly. The printing industry started, which was much cheaper and faster than having monks copy and draw manuscripts by hand. It also led more and more citizens to learn to read, which in turn had an enormous influence on the growth of Western civilization. Coloring of illustrations was still done by hand, as with the woodcut of Buxheim St. Christopher, so named because it was carved in a monastery in this town in southern Germany. Page 500 of Janson’s.

Later, around 1500, the German Albrecht Dürer would bring the art of woodcutting to unprecedented heights. Janson’s chooses the ‘Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse’ as an example, a woodcut now hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is a showpiece from the Northern Renaissance, rooted in the tradition of naturalism. His woodcuts made Dürer famous and rich. He cleverly capitalized on the fear of the approaching Millennium, the year 1500, which was seen by parts of the population as ‘The End of Times’. Dürer added to that by turning the four horsemen from the Book of Revelation into terrifying murderers. Unfortunately, this illustration on page 638 in Janson’s is not clearly depicted on the internet, but can be found elsewhere on the web.

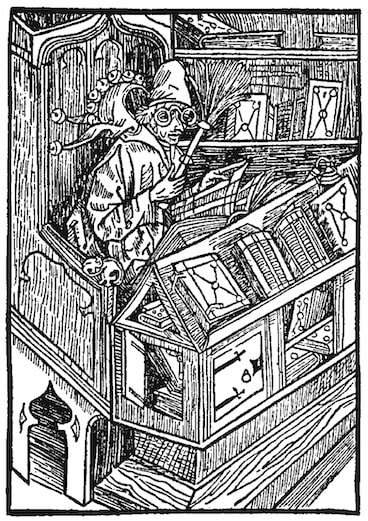

On page 502 Janson’s also shows a work from the same period by Sebastian Brant: ‘Scholar in Study’ from 1494. The title is meant ironically, because instead of a learned monk, Brant carved a fool in wood. The ‘student’ therefore does not hold a quill, but a brush. He does not write or read, but dusts off the books. Criticism of the Catholic Church increased, with Luther later nailing his 95 theses to the church doors of Wittenberg. It all happens during the beginning of the Renaissance, when farewell was taken from the limited outlook of the church. The world opened up and perspective was invented.

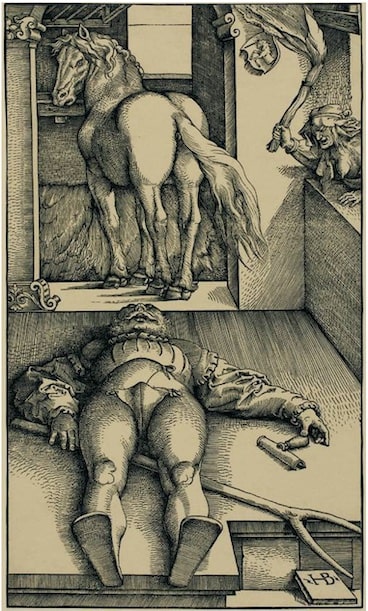

With the decline of the rock-solid certainties of faith came also the fear of witchcraft and heretics, fanned by the Roman Catholic Church. Hans Baldung Grien, a student of Albrecht Dürer, made a woodcut of it. A man lies felled by a spell from a witch-like woman in the window opening. Or did she first bewitch the horse, which then kicked the man to death? Is the witch after his broom, with which she wants to fly through the air? ‘The Bewitched Groom’ from 1544 is on page 646.

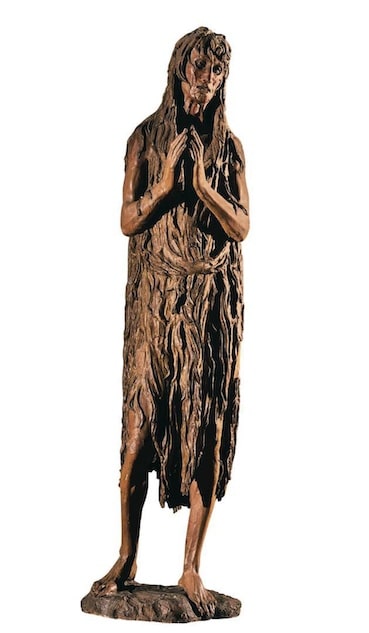

The Mary Magdalene by Donatello is a very special wood carving, life-size, 1.85 meters high. Carved before his death in 1466 from poplar wood, Donatello shows the follower of Jesus in her last years of life, which she supposedly spent alone in the desert, as a hermit. Donatello used the soft wood to express her covered nakedness. Her unkempt hair and a face that is almost a death mask, so decayed and impoverished. Janson’s notes that the artist was less interested in old image forms, but precisely in expressive naturalism. Page 521.

Cassone with the Battle of Trebizond from 1461-1465

Among the shown artistic functional objects, Janson’s now chooses a painted wooden chest by Marco del Buono Giamberti and Apollonio di Giovanni. On page 537 stands this massive wood carving with historical depictions of Venetian merchants who were driven from the Black Sea. The chest (‘cassone’) served as a treasure chest, for storing precious objects.

Another functional object, a clock this time, on page 678. Also carved in Italy, from almost black ebony and other tropical hardwoods. The work of Pier Tomaso Campani and Francesco Trevisiani is dated around 1680-1690. Janson’s points to the architectural elements of this early timepiece. Remarkable is that the time could also be read well in the dark. A hidden oil lamp inside illuminated the Roman numerals. Much to the delight of the owner, Pope Alexander VII, who suffered from insomnia. Unlike most clocks from this period, this specimen also made no or hardly any ticking sounds. In case the Pope might doze off.

Janson’s now takes a jump of almost two centuries, in which no wooden art objects are shown. Those who want to see the harvest of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance will really have to go to hall 1 of the Rijksmuseum.

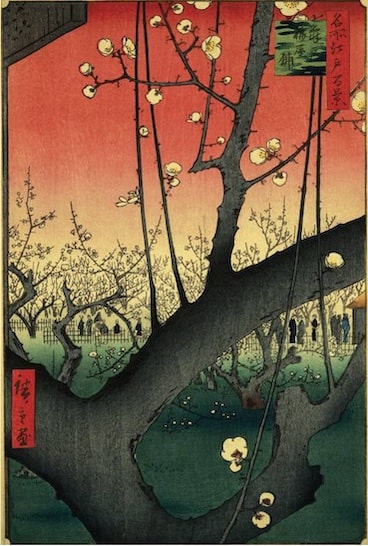

Only on page 871 of Janson’s do we encounter a familiar face. In the Van Gogh Museum hangs a painting by our Dutch grandmaster, who repainted this Japanese woodcut. He was not the only one. In the France of 1850, Japanese art was so popular that people even spoke of ‘Japonisme’. The mysterious country from the East had only just opened up and the world was amazed by the high and refined culture that suddenly arrived in Europe: vases, kimonos, lacquered cabinets, room screens, tea sets. The most fragile functional objects were often wrapped in prints, which artists began to collect. Van Gogh, but also the painters Degas and Manet studied the remarkable way in which the Japanese woodcutters made the distinction between foreground and background disappear, as if there was no near and far.

Janson’s continues to meticulously follow the development of woodcuts. We are now already in 1915, during the art movement ‘Die Brücke’ in Germany. On page 958, a work by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner is depicted as an example: ‘Peter Schlemihl Tribulations of Love’. Kirchner used the centuries-old technique of woodcut to depict with raw cubist forms the inner experience of a man who sold his shadow for a pot of gold. A chaotic composition with bright reds and blues shows his confusion, his discomfort, his psychological conflict when he realizes the consequences of his foolish trade. The influence of African wooden sculptures is evident in this woodcut, especially in the sharp facial features of the man.

And there was Dada with Marcel Duchamp, who tilted a urinal and labeled it as art. Janson’s shows on page 972 another work, ‘Bicycle Wheel’ from 1913. It is nothing more than a wooden stool with a bicycle wheel rotating on it. Duchamp himself was the first to state that this work had no aesthetic value whatsoever. Art historians see more in it. The chair could represent a pedestal and the wheel a human head. And that is again a commentary or reflection on the many busts that populate the museums.

‘The Entombment of the Birds and Butterflies’ by Jean Arp also did not involve a chisel or gouge, at most a jigsaw. Made in 1916-1917, this representative of the artist group Cabaret Voltaire was also a Dadaist. The shape emerged while he was mindlessly drawing. This ‘doodle’ got a very flat, yet three-dimensional form, in which plants, gases or clouds can be recognized. The title therefore only came after the work was sawn out and painted. Janson’s writes that the sculpture can also be seen as a head, suggesting a connection between humans and nature. Page 986.

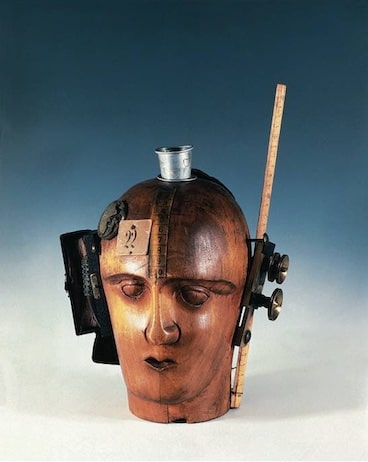

Dadaists really liked wood. Or is it a coincidental selection in Janson’s? On page 988 another highlight, this time a head by Raoul Hausmann, titled: ‘Mechanical Head (Spirit of the Age)’. Made around 1920, this Berlin Dadaist used found objects that were totally foreign to the established art establishment. The wooden mannequin head of a wigmaker, a crocodile leather wallet, a camera lens, the cylinder of a mechanical typewriter, a wooden ruler. Combined it was an ‘assemblage’, an important characteristic of the Dada art movement.

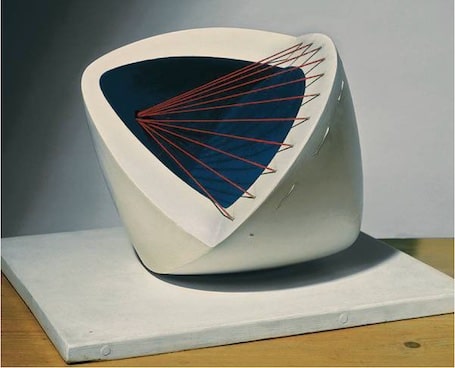

On to the war year 1943. In Great Britain, artist Barbara Hepworth made her ‘Sculpture with Color (Deep Blue and Red), made from a white painted wooden form of 28 centimeters high, with strings stretched on it. It evokes purity, according to Janson’s. The ‘shell’ represents the human mystery that a deep blue sea conceals. The red strings have the intensity of the sun that brings eternal energy and life. Hepworth is a representative of abstract sculpture, to which her countryman Henry Moore is also counted. Page 1003.

Note: it is very questionable whether this shown sculpture actually has a wooden base. The website of Tate states that this Hepworth is made of plaster. Dutch teacher and wood carving enthusiast Hans Westra saw the sculpture in person. He cannot imagine that wood is hidden under the white paint. In the same war year 1943, Hepworth made more sculptures of plaster. Is the editorial staff of Janson’s making a blunder here, or is Tate wrong? Her friend and fellow sculptor Henry Moore, by the way, made similar sculptures with stretched strings on a wooden construction. On Tate’s web page about Hepworth, there are many other magnificent sculptures that are indeed made of wood.

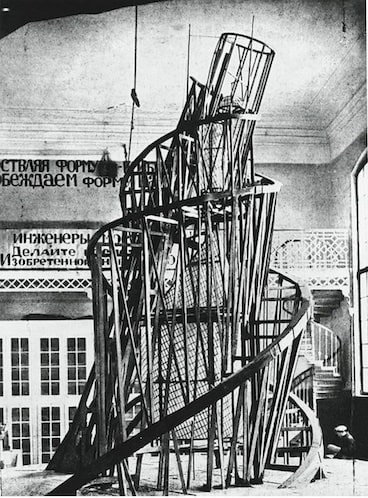

And back again with Janson’s in time, to Russia at the time of the revolution, 1919-1920. Vladimir Tatlin then made a wooden construction as a design for a building, project for ‘Monument to the Third International’. At 6 meters 10 high, it is essentially an abstract composition, inspired by the search for abstraction of other artists such as Picasso and Malevich. This enormous sculpture by Tatlin no longer exists, has never been rebuilt, or built. Janson’s can therefore only show an ugly black-and-white photo on page 1004. The scaffolding the artist had in mind was to be almost 400 meters high.

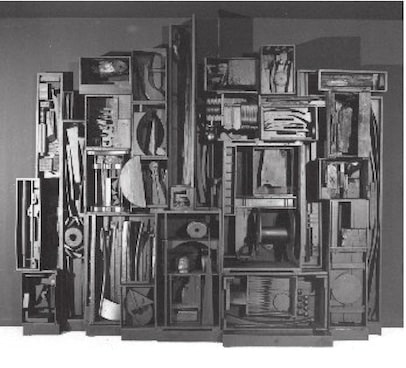

It doesn’t look remotely like Dalí or Magritte, yet according to Janson’s we must also consider Louise Nevelson as a surrealist. In the years 1957-1960 she built this construction of three meters height, full of black-painted objects. ‘Sky Cathedral – Moon Garden Plus One’ is a stacking of wooden boxes stuffed with wooden shapes. It could be a repository of civilization, but also a cosmos with planets and moons, splintered wood representing mountains. Nevelson sets the whole in blue light, suggesting the hour of twilight, when day transforms into night and all things begin to look different. Swallowed by mystical forces. According to Janson’s, on page 1042.

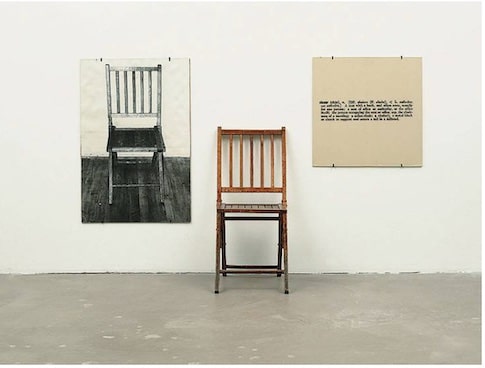

Wood carving skills were also not needed by conceptual artists. The idea was more important than the execution. That certainly applies to the work ‘One and Three Chairs’ by Joseph Kosuth from 1965. It consists of a wooden folding chair, a photo of the same chair and an enlargement from a dictionary explaining the word chair. On page 1062, Janson’s explains that by using words instead of an image, Kosuth makes clear how cerebral his intentions are.

Post-minimalism. Under this art movement, Janson’s classifies Martin Puryear, who in 1985 made a construction of over two meters in length from steel, pine and cedar wood: ‘The Spell’. Art historians particularly notice the craftsmanship qualities of his work with wood. The beauty of the curved forms, the elegant covering of the horn. The warmth of an organic object. Trained by woodworkers in West Africa and Japan, countries with a long tradition in woodworking, his work even reflects his African-American background. What does this artwork represent? Is it a trap? Or primarily a form? Judge for yourself on page 1090 of Janson’s.

The second to last shown artwork with wood in this edition of Janson’s is a large work by the American David Hammons from 1982: ‘Higher Goals’. It is reminiscent of the totem poles of the original inhabitants of America, but non-Western art is completely absent from this standard work. It serves at most as a source of inspiration. Yet the story on page 1096 behind this artwork is beautiful. Hammons encountered a group of teenagers in his neighborhood Harlem in New York who were playing basketball on the street during the day. When he spoke to them about it, they told him that not school, but sports was the only path to success. In response, Hammons made four enormous wooden poles of 12 meters high, with the basketball net in the top. As decoration, he used, among other things, the caps of alcohol bottles, because of the association with drunkards and losers. Aim higher, then you’ll get further, is the artist’s message.

On the actual canvas of 2.79 by 2.79 meters, the central woodcut is immediately visible, in black and white. It is a tomb, a mausoleum for painters. German artist Anselm Kiefer made the work in 1983 and thus added another new application to woodcut art, with this mixed technique of oil paint, emulsions, shellac, straw and latex. Also in this work, ‘romanticist’ Kiefer comments on German history, through the vigorous flowing movement toward the grave monument. This stands unapproachable in black and white, stained with blobs of paint. Janson’s sees it as a reflection on the German tradition, and how Hitler abused it by labeling the work of modern artists he didn’t like as ‘degenerate art’. On page 1086.

All in all, it is a meager harvest of illustrations, even though the medium wood is always discussed in the text itself. If this Janson’s is the standard work for curators, museum directors, art institutions and education, selection committees and subsidy providers, then it is not so strange that quite a few contemporary artists who work in wood – or derived materials such as paper pulp – receive less attention than they deserve. Or even have to operate in the margins of the established art circuit.

Web tip: on the internet, the mentioned page numbers of Janson’s can be consulted here.