Gauguin missed the bisj poles. In search of authentic woodcarving in Polynesia, he would have been better off traveling to Papua New Guinea than to Tahiti. In this former Dutch colony, the culture of carving bisj poles was still thriving around 1890.

Gauguin missed the bisj poles. This pole is shown in Paris, in Musée du Quai Branly.

When the French painter Paul Gauguin traveled to Tahiti in 1890, he was driven by a desire for origin. He searched for an art untainted by academic rules, perspective, and rationality. His ideal was an art still connected to myth, body, and nature. Wood played an important role in this search.

To his great disappointment, Gauguin discovered that the woodcarving traditions in the French colonies had largely disappeared. Colonial authorities and the Roman Catholic Church had banned, removed, or destroyed many of the ritual images of the South Seas. Gauguin therefore decided to reinvent the tradition himself, incorporating Polynesian motifs into his own masks and sculptures.

An original wood tradition

When these works were exhibited in Paris, they caused a sensation. His sculptures carved directly in wood were eclectic and personal, blending Polynesian ornament with European artistic traditions and his own invented mythology. Visionary, certainly, but not a continuation of a living woodcarving tradition.

Here the contrast with Papua New Guinea becomes clear. In the southwest of the island, among the Asmat people, a vital and uninterrupted tradition of monumental woodcarving still existed around 1890. The famous bisj poles were not decorative objects, but ritual sculptures created for a culture that was very much alive.

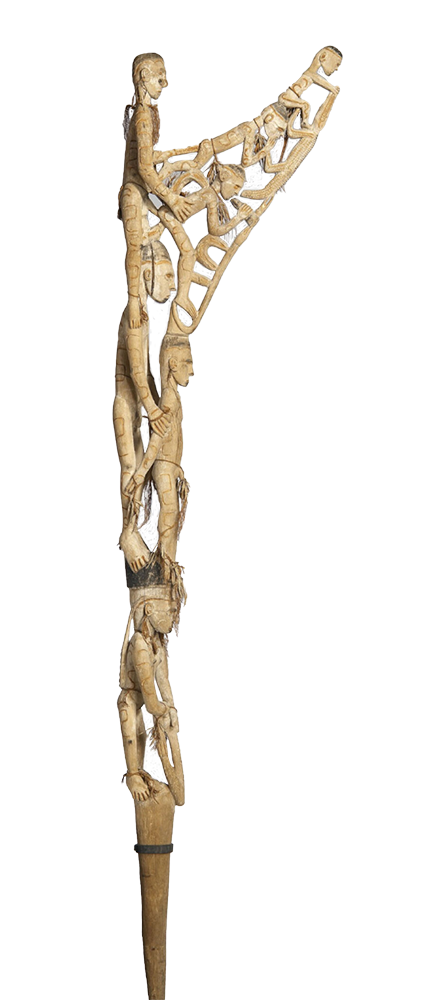

The top of a Bisj pole from the Asmat people, Papua New Guinea.

Bisj poles were carved in honor of deceased clan members, as part of extensive mourning and commemorative ceremonies. According to the Asmat worldview, every death disturbed the cosmic balance. Carving a bisj pole helped to restore that balance.

The poles were carved from a single tree trunk, often mangrove wood. Unusually, the thick root end was oriented upward, meaning the trunk was worked in reverse. Into the wood, carvers cut stacked human figures representing specific ancestors. Older generations appear lower on the pole, while more recently deceased individuals are placed higher.

At the top of the pole there is often an openwork projection, known as the cemen. This element refers to fertility, strength, sexuality, and the continuation of life.

The carving style is rhythmic, direct, and uncompromising. There is no use of linear perspective or anatomical correction. Meaning is conveyed through repetition, gesture, and vertical structure.

Sculpture meant to disappear

Bisj poles were never intended to last forever. After the rituals, they were placed in the swampy sago groves, where they were left to decay. Their decomposition fed the earth both symbolically and literally. For the Asmat, wood was not an autonomous art material, but a temporary carrier of memory, obligation, vengeance, and reconciliation.

Bisj poles were traditionally placed in sago forests after rituals and allowed to decay naturally.

If Gauguin had encountered this tradition, he might have found exactly what he was searching for: wood as memory, form as ritual, and art as a social act. The vertical stacking of figures, the fusion of life and death, and the emphasis on sexuality and reproduction are precisely the themes Gauguin sought and obsessively depicted. But he no longer encountered them as a living tradition in French Polynesia.

Bisj poles in the collection of the Wereldmuseum Amsterdam, collected during the colonial period of Dutch New Guinea.

That bisj poles are now visible in Dutch museums, such as the Wereldmuseum in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, is due to the colonial history of Dutch New Guinea. In Amsterdam, I saw a remarkable series of bisj poles, often older than those collected by Rockefeller and now displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Dutch administrators, missionaries, and ethnographers collected these works earlier, including in the years before and after 1900, often out of fear that the culture would disappear. Ironically, the bisj poles survived precisely because of this relocation, even though they were originally meant to decay quickly in the humid tropical climate.

A comparative note: the Makonde

As a final note, in Tanzania and Mozambique another people, the Makonde, carved wooden sculptures that recorded family histories, often known as Tree of Life figures. I previously wrote about these works in an overview of African woodcarving.

There is, however, no evidence of mutual inspiration between the Makonde and the makers of the bisj poles. There are no historical records of trade, migration, or ritual exchange between these regions. Both cultures developed their woodcarving traditions independently, within their own social and ritual contexts.

Jan Bom, Februar 8, 2026