Burning ballerina refers to the historical phenomenon of ballerina costumes that could easily catch fire. Gas lamps used to serve as dangerous stage lighting. The dramatic consequences: severe burns and even the death of a dancer. Being a ballerina used to be a life-threatening profession.

Burning ballerina, with a skirt of burned spruce wood (Cross Laminated Timber (CLT)).

The most striking example is the tragic death of French ballerina Emma Livry in 1862. Livry’s accident was caused by a gas lamp that set her skirt on fire during a rehearsal.

The costumes of ballerinas were made of light muslin and tulle; highly flammable fabrics and therefore very risky. In the 19th century, gas jets were simultaneously used for stage lighting. Ballerinas had to stay well clear of them. However, other light sources did not yet exist, so from a safety perspective the costumes were adapted.

Ballerinas initially resisted fire-retardant treatments of materials. This made their skirts stiffer and less airy. The respected ballerina Livry also refused to dance with ‘treated’ skirts.

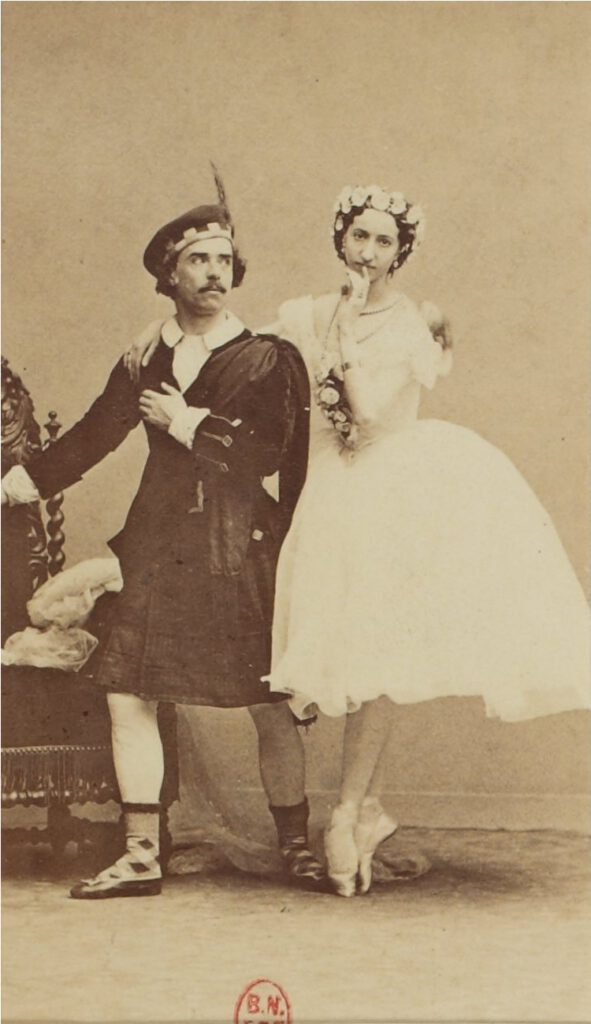

Emma Livry with a fellow dancer, before the fatal fire.

If only she had been wiser. In November 1862, during a rehearsal for the Paris Opera, a gas lamp set her skirt on fire. Livry first tried to extinguish the flames herself, without calling for help from stagehands. In vain.

After she was taken to the hospital, her corset had melted onto her body. It was therefore too painful to remove. Livry died months later, in July 1863, from complications of her burns.

Stricter safety

Livry’s death led to stricter safety standards in French theaters. In addition to adapted skirts, there were also fire-retardant measures and safety measures such as the presence of wet blankets and fire buckets.

The ‘Burning ballerina’ became a symbol of the dangerous and often fatal reality of the romantic ballet era. It is now an almost forgotten reminder of the years before the advent of electric light. The burned remains of Livry’s costume still hang in the Musée de l’Opéra in Paris. This keeps the memory of the once life-threatening dance career of ballerinas alive.

Source of inspiration for the ‘grand écart’ pose of my sculpture of the Burning ballerina.

Have we become wiser from this? History keeps repeating itself, in new forms. The resistance among some employers and professional groups to introducing safer work materials is just as current as in 1862. A well-known example is the opposition among painters to exchanging paint based on volatile substances for water-based paint. The resistance of truck drivers to the introduction of the tachograph to prevent excessively long working hours is another example. Very current is the dramatically poor legislation and regulations regarding the use of controversial pesticides by farmers – and citizens. The Dutch bulb growers are a symbol of this, who put their own health and that of their surroundings at risk.

Skirt burned with gas torch

I also burned the skirt of my wooden sculpture ‘Burning ballerina’ with a gas torch. It couldn’t be more symbolic. The wooden base consists of composite spruce wood, so-called Cross Laminated Timber (CLT), also called ‘cross wood’. Large industrial wood factories assemble enormous panels from perfect spruce beams: walls, roofs, pillars. Complete houses and offices and even fire stations are built with these pre-fab parts. Windows and doors are sawn out of the panels in advance at the factory. I was allowed to take a car full of this ‘industrial waste’ from the Derix factory in Germany, to make my sculptures from.

That did give me headaches at first. Spruce wood is terrible wood for carving beautiful figures. It splinters, cracks and after modeling cannot really be made smooth with rasp and sandpaper.

Burning ballerina’s skirt, the soot layer already partially brushed off with a copper brush.

But the wood does hide a special property. It comes from fast-grown conifers, cultivated in plantation forests. The soft parts between the annual rings are therefore much larger than those of a tree that grew slowly in a natural forest. These soft parts of spruce wood burn much deeper than the annual rings when you apply a gas torch to the sculpture.

After brushing away the shiny black layer of charcoal, a beautiful natural pattern in the wood emerges. The skin of the wood also turns out to be very smooth after burning, while remaining very rough on the end grain sides. Beautiful, I think. The crosswise glued beams also create an extra erratic pattern, very varied.

The body of my ‘Burning ballerina’ is carved from the sapwood of American walnut. It is very light in tone and can be sanded beautifully smooth. I love the almost black-and-white contrast with the burned skirt of the ballerina, who poses in a difficult split position: the grand écart.

Jan Bom, September 22, 2025

Postscript. After I presented my ‘Burning ballerina’ on Facebook, the sculpture was sold within 4 hours. The new owner Pascalle Quaden came to pick up the sculpture personally and was very happy with it.