The Italian sculptor Giacomo Manzù made more than 50 cardinals in his lifetime, almost all cast in bronze. But one special version he carved in wood, in 1945.

Our writer-sculptor Jan Wolkers received lessons from Manzù. And made love in the cinema with his later wife Inge, a young German dancer. It is a salacious footnote in art history.

The first Cardinal Seduto

A search on the internet for wooden sculptures by what the Italians themselves call the greatest sculptor of the last century ends without success (the even more famous Giacometti was Swiss). There is only one image of Giacomo Manzù to be found, presented by the London gallery RKade. The British sold the work ‘Cardinal Seduto’ for an unknown amount. It is signed by the master himself, 88 centimeters high and with an elegance you would not expect from a former carpenter’s apprentice. The long fingers on the lap of the wooden cardinal are even reminiscent of the refinement of Balinese Art Deco.

Manzù was born on December 22, 1908 as Giacomo Manzoni in Bergamo, as the son of a poor shoemaker. He never received a formal art education. He first learned the craft from a carpenter and later from a wood carver, where he carved sculptures for churches. A gilder and a plasterer perfected his skills. With his talents he had thus packed enough knowledge in his backpack to become a professional sculptor. And later he even became ‘professore’ at the Art Academy in Milan for years.

First the young sculptor Manzù copied traditional sculptures in his birthplace in Northern Italy, still a cradle of contemporary wood art – especially in South Tyrol. He left without a penny in his pocket for Paris, where after twenty days he lay on the street nearly starving to death. Manzù was sent back to Italy by the police. There he got the chance of a lifetime, when architect Giovanni Muzio gave him the commission to decorate the chapel of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, a job he worked on from 1931 to 1932.

It earned him so much fame that not much later he could organize an exhibition of his works in Rome. And there, in Vatican City, he saw the Pope with two cardinals, including Cardinal Seduto. That man, in his wide mantle and his mitre on his head, he continued to capture in sculptures for the rest of his life, mainly in bronze. Serious versions. Cheerful ones. Minimalist ones. And thus that one in wood, right after the end of World War II.

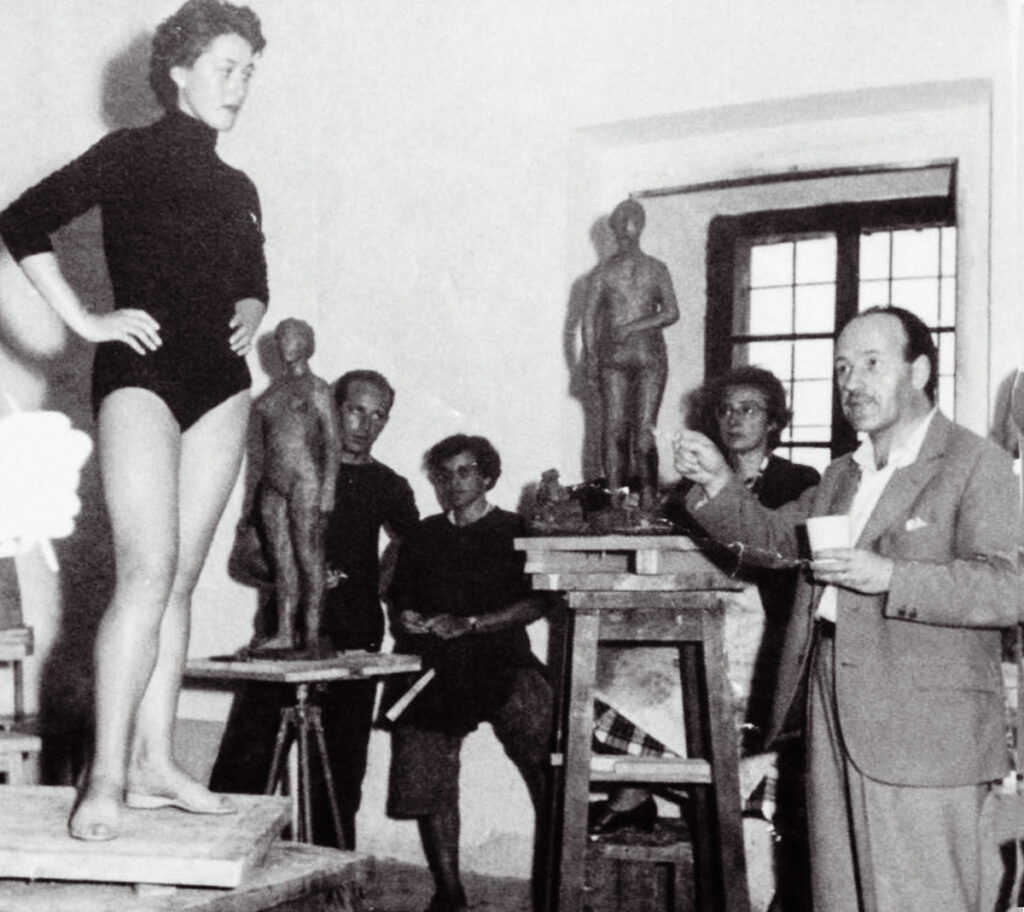

Giacomo Manzù gives lessons in sculpting, his German muse Inge poses for his students.

Manzù was already a celebrity in 1954, with the International Prize of the Venice Biennale in his pocket, when the sculptor-in-training Jan Wolkers was allowed to take a month of lessons with him in Salzburg. Onno Blom devotes a chapter to it in his Wolkers biography ‘Het litteken van de dood’, titled ‘Geheime Liebe’.

‘The legacy of the Renaissance’

At the Sommerakademie für Bildende Kunst of Oskar Kokoschka, Wolkers meets Manzù and writes condescendingly to his wife: ‘Manzù has the appearance of a fat little café owner who raises the bill when he thinks the man and woman sleeping in his hotel are not married.’

Of that first impression nothing turned out to be true. Wolkers came back to it: ‘You saw how he set up a portrait or a nude from the beginning, built it up, and, virtuoso that he was, with the legacy of the Renaissance in his fingertips, perfected it in a short time. (-) He is shockingly skilled.’ Wolkers also sees a sculpture by Manzù of a cardinal and finds similarities with his own Biblical sources of inspiration.

‘A classical head’

Manzù in turn was also very pleased with his Dutch student. In class he showed a work by Wolkers to the other students as an example: ‘This is now a classical head.’ Wolkers became the best in his class.

The master also taught his students to model sculptures of women. He invited dancers who were in Salzburg for the Festspiele. One of them was the very young and beautiful Inge Schabel from Munich. Wolkers made sketches of her. Naked, seen from behind. High on her legs and the head slightly bent. Also of her face. ‘An entzückendes creature’, Wolkers remembered later. In translation that means: adorable.

‘Didn’t see any of the film’

Inge asked Wolkers to go to the cinema, where the film ‘Geheime Liebe’ was playing. In the lead role the prim blonde film star Doris Day. It was a very hot summer day.

Wolkers wrote: ‘Before the film started, our clothes were already hiked up in all directions. We sweated so much that I wondered if the lens of the projector that shot its beams of light into the hall just above us would fog up from it. Her armpit became a little bowl of moisture. It tasted just like the water from the mountain streams that flowed along the slopes in the area around the town, where you always had to be careful when scooping up a handful not to slurp down a larva of a fire salamander. I didn’t see any of that film. I only occasionally heard the perky maid’s voice of Doris Day. And she kept moaning geheime Liebe at every kiss and caress.’

A long series of Inges followed

Wolkers never saw Inge again after that, except in the drawings he had made of her. He told his biographer Blom that he had kissed the drawn mouth of Inge so often that no more than a smudge remained of it. His already poor marriage to the Zeeland beauty Maria de Roo went to ruin for good.

The also already married Manzù in turn also conquered Inge. To all his cardinals the Italian then added a long series of dancers to his oeuvre, always with Inge as his graceful model. Wolkers only found out about this ten years later, when Manzù received the commission in Rotterdam in 1968 to make two bronze doors for the Laurenskerk. From an accompanying book Wolkers understood that the already thirty years older Italian artist had found an inseparable muse and life partner in Inge. She would stay with him until his death in 1991.

‘A cowardly hero tenor from the opera’

The image of the Italian master tilted again in Wolkers’ head. ‘His curls are too shiny and orderly and his gaze too piously meaningless. He looks like a cowardly hero tenor from the Italian opera.’

The head of the wooden Cardinal Seduto by Giacomo Manzù, with mitre.

The love battle between Jan Wolkers and Giacomo Manzù today recalls the entertaining books and films about Don Camillo. They appeared at the same time as the meeting between the Italian and the Dutchman. The stories are about a robust village priest who is constantly at odds with the mustachioed communist mayor. The setting: a village on the Italian river Po. Wolkers, himself charmed by communism, could thus take on the role of mayor Peppone. And Manzù, with his eternal cardinals, that of the village priest who didn’t always take his faith so seriously.

Jan Bom