Katsura Funakoshi brings Japanese to life. His wooden sculptures breathe a serene beauty. With a masterful command of classical Japanese wood carving techniques, he gives his figures a lifelike presence. Also because the marble eyes seem to look at you.

Katsura Funakoshi brings Japanese to life, like this woman in the sculpture Hands Can Reach the Sea.

Katsura Funakoshi (1951–2024) shows his people mostly as half-figures, from the waist to the head. The marble eyes in the face radiate an almost hypnotic, calm gaze. The combination of wood and marble makes the sculptures striking: as if they simultaneously show an inner world and an outer world.

His approach reflects a deep belief in human experience as something that deserves space and stillness. There is also a need for this in the Western world of fast, superficial impressions. Funakoshi’s sculptures are expensive; between 45K and 90K with a top price of 185K at auction house Sotheby’s for Black Mountain. But affordable giclée prints of his wooden sculptures are offered via the internet.

Eyes of painted marble

One of his earliest known works — such as The Day I Go to the Forest (1984) — already shows his mastery. The fineness of the clothing, the visible traces of his chisel, and the natural wood grain bring his busts to life. Moreover, this wanderer radiates an almost philosophical calm. The work is part of the collection of the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo.

I looked up how he did that, placing those marble eyes. He first carved the head completely, only then working out the eye sockets with great precision. The marble eyes were separately ground and made to fit exactly, so they could be placed in the wood. Then Funakoshi fixed the eyes with a traditional animal glue, a technique that goes back to centuries-old Japanese sculpture practices. Subsequently he carved the eyelids so refined that they still enclose the marble eyes, so that no technical intervention remains visible. Finally Funakoshi applied thin layers of pigment to the marble, usually to accentuate pupils and irises, or to add a very light tint that makes the reflection of the eye more natural. He never painted a full color layer; it was more a delicate nuance, so that the marble texture remained visible. The effect: the eyes seem to have emerged from the wood itself. Very skillful.

Katsura Funakoshi brings Japanese to life

Interesting fait divers: it is known that Funakoshi sometimes took the train to study the staring facial expressions of fellow passengers. Since I read this, I cannot think of his figures other than as people looking at the passing world outside through a train window.

The Day I Go to the Forest, one of Funakoshi’s early works.

Aromatic camphor wood

Born in Morioka in Iwate Prefecture, Funakoshi came from an artistic family. His father was himself a respected sculptor. This familial background brought him into contact with the world of sculpture at an early age.

Funakoshi studied at Tokyo Zokei University and continued his education at Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. In the early 1980s he began to specialize in wood carving of human figures from camphor wood (kusu) — a wood species known for its rich texture and aromatic scent. I don’t know many other wood artists who choose this wood species, which was also used in the past to build ship’s chests. The scent kept moths away. Funakoshi left the grain of it visible and vibrant. He also often left part of the head or crown unpainted to accentuate the natural beauty of the wood.

Not too childish

Winter Book (1988) is a well-known work from Funakoshi’s oeuvre that has been shown in exhibitions and gallery presentations.

What distinguishes Funakoshi from quite a few other modern Japanese wood carvers is that he stays far away from the in my eyes often childish animal figurines or little girls with big doll-like eyes. (My criticism certainly does not apply to old Japanese masters like Unkei c. 1150 – 1223, who placed glass eyes in his sculptures, a practice that Funakoshi thus adopted from him).

Although Japanese, Funakoshi’s figures are universally recognizable. Also beautiful that he sometimes places his half-figures on four curved branches, as a kind of tall pedestal. That combination of worked with unworked wood relates Funakoshi to Dendroism, where the form of the wood tells its own story.

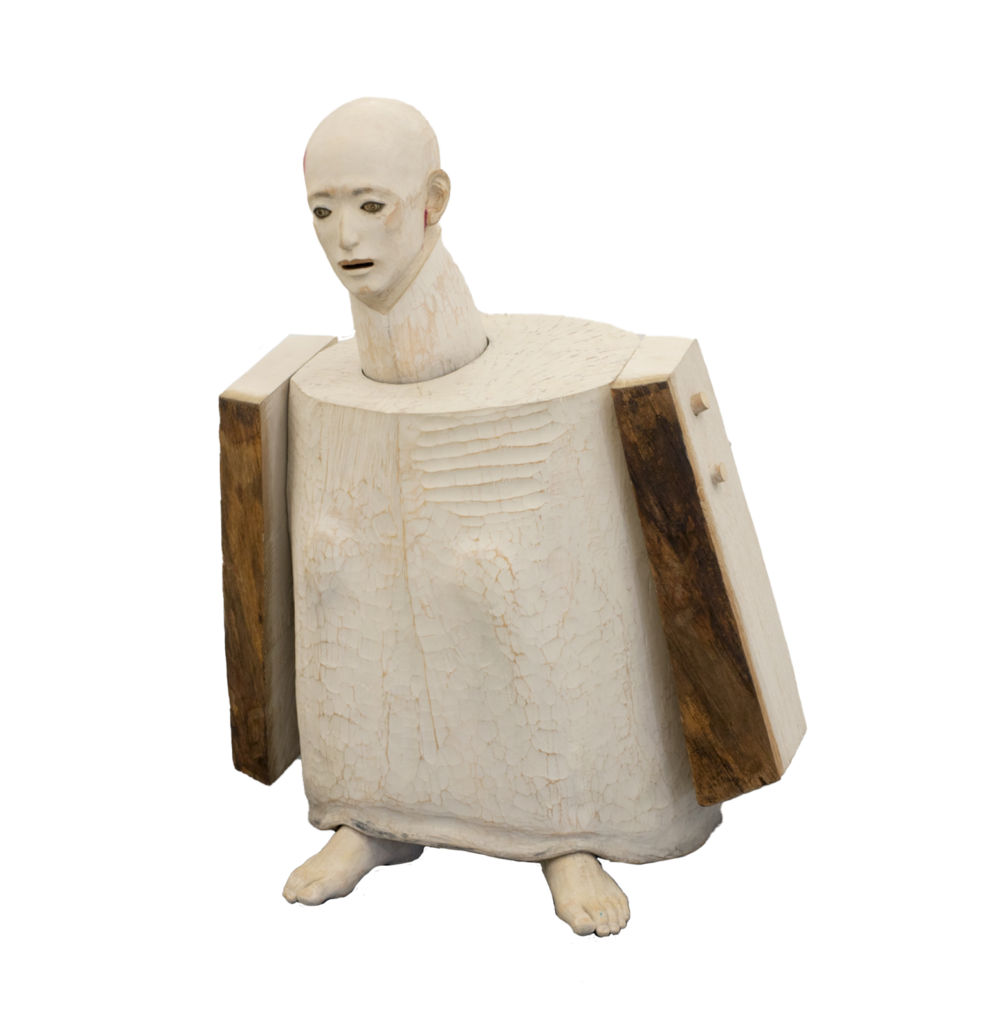

Dancing as a Puppa (2001), a hybrid sculpture: half human, half bird.

I also find it fascinating to see how his imagination went further and further. In the 1990s he began a series in which human and animal forms merge into hybrid figures — symbolically charged sculptures that raise questions about identity, humanity and nature. Dancing as a Puppa is such a sculpture from 2001, in which the half-total suddenly has feet, but also two side panels attached with wooden pegs, which resemble the wings of a bird. Somewhat surrealistic too.

Funakoshi worked hard and built an impressive oeuvre of more than one hundred sculptures. In Tokyo several of his works can be seen in museum collections. Although museums often exhibit on a cycle basis , pieces from his figurative portrait series — such as Winter Book, Hands Can Reach the Sea and Moon Shining on Forest — are among the best known and most admired works from the Japanese collection. Yet quite a few of his works, especially drawings, are still for sale on Artsy, the collector site for art galleries.

Japanese voice at Biennales

His sculptures are appreciated not only in Japan, but also internationally. Funakoshi represented Japan at the Venice Biennale (1988), the São Paulo Biennale (1989) and Documenta IX (1992). His sculptures are included in major collections such as the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Funakoshi received various awards for his work, including the Medal with Purple Ribbon — one of the highest artistic honors in Japan. He died in March 2024 at the age of 72.

Jan Bom, January 27, 2026