The heads of Jean and Sophie Arp are two artworks by a pioneering artist couple. Sophie made the first, famous DaDa Head around 1919. Jean followed ten years later with Two Heads, as one of his also famous series of abstract wooden reliefs, built up from organic, colored planes.

The heads of Jean and Sophie Arp, left the wooden relief by Jean, right the wooden bust by Sophie.

Jean Arp (also called Hans Arp, 1886–1966) was a leading French-German sculptor, painter and poet, best known for his contribution to the DaDa and Surrealism movements. But Arp’s career cannot be seen separately from his wife: Sophie Taeuber‑Arp.

The great DaDa love couple

She was a versatile Swiss artist who was just as groundbreaking in modern art as he was. In recent years her previously undervalued work received ample attention in museums, including an exhibition at the MoMA in New York in 2022. It fits the trend in the art world to balance the work of women with art made by men.

Sophie Henriette Gertrude Taeuber was born on January 19, 1889 in Davos, Switzerland. She studied applied arts and textile design in Germany and returned to Zürich in 1915. There she met Jean, who had settled in Switzerland to avoid service in the German army. From their meeting grew an artistic and personal bond that would result in a marriage in 1922. Jean and Sophie became the great DaDa love couple.

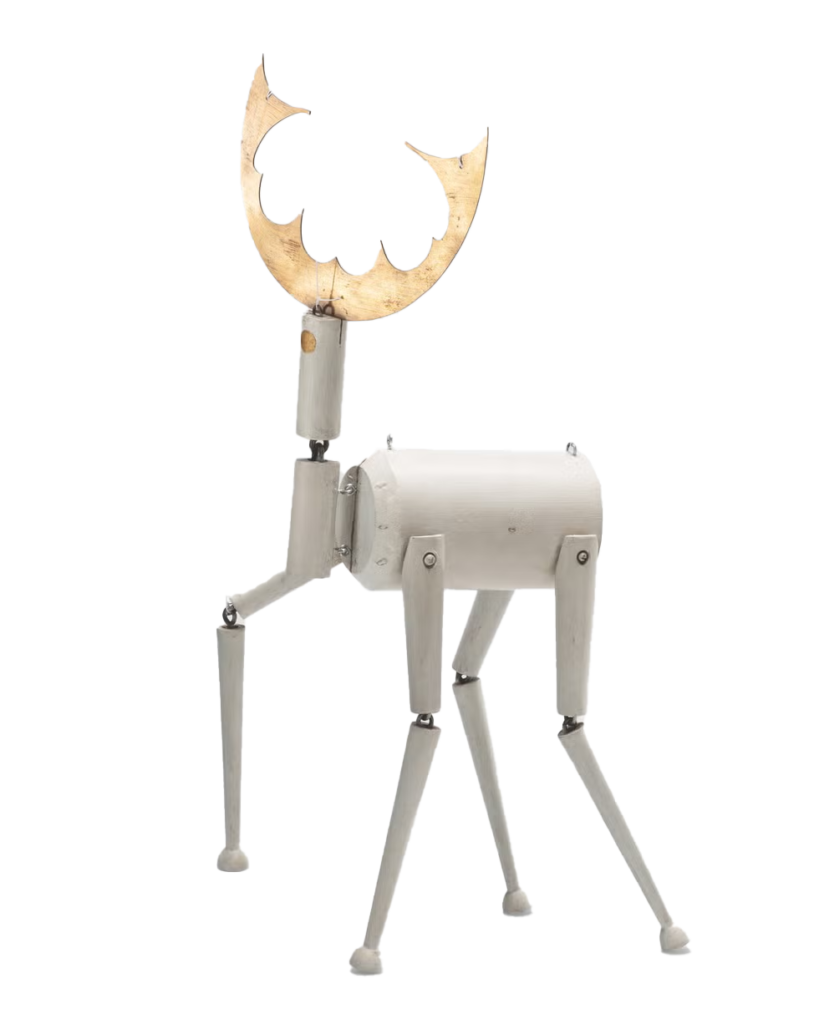

Wooden deer by Sophie Arp, one of the marionettes she made for a theater performance.

Besides her visual work Sophie was closely involved in dance and performance. She studied modern dance and performed in Dada performances at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich, the birthplace of DaDa, where she also met Jean. DaDa was an art practice that embraced randomness as creative force. It became a starting point that Arp would continue to apply in all his work.

Against the absurdity of war

The Cabaret Voltaire was founded in 1916 as a platform where writers and artists could protest against the absurdity and waste of the First World War. (The name Voltaire referred to the great philosopher of the Enlightenment whose ideas embodied the logic that the Dadaists attacked).

The artists and writers of the Cabaret Voltaire attacked the rational thinking that they believed had produced the corrupt civilization responsible for the war. Their target was all established values – political, moral and aesthetic – and their goal was to overthrow the old bourgeois order with nonsense and anarchy. Ultimately they hoped to create a tabula rasa, a clean slate, that would form a new basis for a fresh view of the world.

Marionettes became art sculptures

In 1918 Sophie received from the director of the art school where she taught (the Zürcher Kunstgewerbeschule) the commission to design marionettes for a modern performance of Carlo Gozzi’s The King Stag. Sophie created wooden puppets built from geometric shapes — cylinders, cones and spheres — with visible hinges and connections. These marionettes reflected her sense of rhythm, movement and space. The puppets were a synthesis of her experience in dance, sculpture and design. They were praised for their inventiveness and playful exploration of form and mechanics. Very different from traditional wooden and folkloric marionettes, of which Pinocchio became the most famous.

Especially the deer from this performance became a beautiful sculpture, I think. Nice to compare Sophie’s golden antlers with those of the man-sized wooden deer by Zadkine, which I saw in the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Sophie Arp behind one of her Dada Heads.

Shortly after the marionettes Sophie also made from 1918 to 1920 a series of wooden heads (DaDa Heads): colorfully painted, stylized sculptures that characterize the humor and experimental nature of DaDa. One of these heads is a portrait of Jean Arp himself. These works show how Sophie combined wood carving (or rather: wood turning) with abstract geometry. She thus bridged applied art and avant-garde sculpture.

The organic processes of Arp

Jean Arp in turn became especially famous for his biomorphic works full of flowing forms. They seem to be depictions of organic processes — buds, shells, leaves — but they are completely abstract. These forms reflect Arp’s conviction that art should not depict nature, but should experience it. His works suggest growth, transformation and rhythm. They thus touch on the unconscious and the mythical, two core ideas of Surrealism, the art movement that followed DaDa in 1924 – and still exists after 100 years.

Even the relief Two Heads in the MoMA in New York (pictured above) by Jean reminds me more of water lily leaves and a tropical plant than of the heads of two people. Through the title you yourself fill in the top relief layer as human hair. Not surprising, because Arp did this in other sculptures too with a mustache, like the hardboard collage Moustaches that is owned by the Tate in London.

Impish Fruit, a relief from 1943 by Arp in unpainted chestnut wood, in the collection of Tate in London.

Although Arp worked in various materials — from paper and collage to bronze and plaster — wood played an important role in his early sculptures. Around 1917 he began with abstract wooden reliefs, in which colored planes evoke visual poetry. These reliefs are early examples of his search for form independent of representation, a search that would later profoundly influence his three-dimensional sculptures. (And sometimes he later returned to those early wooden reliefs, like the unpainted ‘ironic fruit bowl’ Impish Fruit from 1943. Naturally that is my favorite.)

Sculptures based on Doodling

Jean Arp too, like his wife, can certainly not be called a traditional wood carver. The forms of his low reliefs were based on mindless drawings, ‘doodling’. He gave those scribbles to a woodworker who sawed out the shapes for him, after which he painted them and put them together. He invented the titles only afterwards, like The Entombment of the Birds and Butterflies (Head of Tzara).

Jan Bom, January 11, 2026.