Top 10 African Wood Carving Traditions is not a list of individual masterpieces. It is more of an overview of the ten most important African wood carving traditions, each represented by typical sculptures or masks, to showcase the diversity and ritual significance of these cultures. In almost all African wood carving cultures, sculptures never exist as a single unique specimen, but are part of a larger typology or tradition.

African wood carving functioned primarily within social ritual and spirituality, with emphasis on community, leadership and ritual function — rather than on individual authorship as in Western art after the Middle Ages. The fact that many makers remained anonymous reflects this different art paradigm, not a lack of quality or creativity.

What these traditions have in common is that African sculptures are usually made of wood. The sculptures are spread across the world in ethnographic museums and art collections. And because many African masks are quite affordable, art objects can also be found with many private collectors. Here is my top 10, in no particular order.

1. Makonde (Tanzania/Mozambique)

The Tree of Life sculpture is a traditional narrative and symbolic object in which human figures from one tribe or family seem to grow from the trunk of a tree. They are often carved from a single piece of ebony trunk (African blackwood) — a wood species that is abundant in East Africa and beloved by Makonde carvers for its density and deep color. I love this narrative carving style; it was also the first African sculpture I bought, carved from a rather crooked branch of ebony, where the white sapwood is still visible. It creates a striking contrast.

Examples can be found on sales sites like Etsy.

2. Kuba (Congo)

Kuba wood carving is known for royal portraits (ndop), ceremonial staff figures and symbolic ornaments. They display power, prestige and ritual authority. The wood is so dense that the sculpture almost looks like bronze. But it is not.

This example can be found in the Brooklyn Museum.

3. Dogon (Mali)

Dogon sculptures and masks play a central role in rituals around ancestor worship and the dama dances. They combine abstract and symbolic forms with expressive ancestor figures. These are very dynamic sculptures, especially when men ride horses with front legs like human legs including male genitalia.

Examples can be found in the Metropolitan Museum.

4. Yoruba (Nigeria)

Yoruba wood carving includes royal, religious and initiation objects, including complex helmet masks (Magbo) that visualize social and religious hierarchy. But everyday objects were also beautifully carved, like this small chair. Yoruba artists work not only in wood and remain influential today.

An example of a panel with figures can be found in the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

5. Bamana / Dozo (Mali)

The Chiwara figures are abstract antelope forms that play a role in agricultural rituals. Their geometric lines and diagonal compositions symbolize ritual and cosmic order. Wow, what stylization this culture from Mali mastered. I bought two beautiful masks in the capital Bamako on a work trip, but I would trade them in a heartbeat for this sculpture.

Examples can be found in the Metropolitan Museum.

6. Baule (Ivory Coast)

Baule wood carving is known for ancestor portraits and complex ritual figures. They emphasize human expression, beauty and ritual meaning in ceremonies. On to one of the most iconic museums in Paris, one of the first buildings in the world to have a vertical garden installed on a facade. I wrote a Special issue of P+ about it. But unfortunately had no time to go inside.

A beautiful, extensive collection of African art can be found at Musée Quai Branly in Paris, including Baule wood carving.

7. Luba (Democratic Republic of Congo)

Luba wood carving includes caryatid stools, relief sculptures and ceremonial objects. They display refined composition and ritual leadership, often with feminine symbolism. Lovely to fall asleep on such a romantic headrest.

This example also belongs to the collection of Musée Quai Branly.

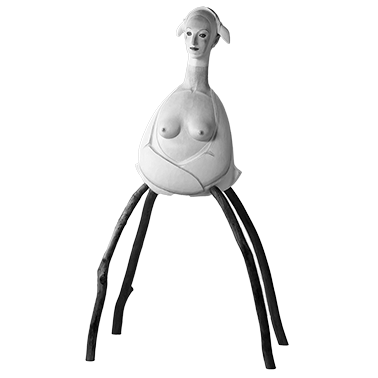

8. Chokwe (Angola / Congo)

The Chokwe create refined masks and figurines that fulfill social and ritual functions. They combine realism with abstract patterns and symbolism. Both Picasso and Brancusi were inspired by African artists, which both denied. Yet one could argue that Picasso’s ‘African period’ was the prelude to Cubism. And that the pedestals Brancusi made looked very much like African wood carving and grew into his world-famous Endless Column.

Many Chokwe masks are offered in trade, but this sculpture is from the MoMA in New York.

9. Fang Ngil Masks (Gabon)

Specifically the white masks of the Ngil society, used in initiation rituals and to ward off evil influences. They represent a highlight of Fang aesthetics and ritual design. Recognizable from thousands, these elongated heads. Beautifully stylized: how the nose continues into the mouth without being disturbing.

These masks are still available at galleries such as African Arts Gallery.

10. Dogon / Bamana Variants

This category includes other ritual masks and figures that do not fit into the previously mentioned types, but are typical of the symbolic and ritual use of wood in West Africa. They show the enormous variation within one culture. The sculptures were used in initiation rituals and to ward off evil influences. They represent a highlight of Fang aesthetics and ritual design.

A beautiful Bamana mask with shells can be found in the Metropolitan Museum.

Inspiration for European Artists

In this top 10 I show sculptures by anonymous African artists who inspired their famous European colleagues. But it could also be that different cultures independently recorded the same themes in wood, without knowing each other’s work. Take for example the Polynesian wood traditions: there are striking parallels with the African Makonde. The genealogical visual language and the ‘growing’ figure compositions on the Pacific islands strongly resemble the Makonde motif of the tree of life. Yet I dare not claim that these traditions ever knew each other before, especially given the enormous physical distance.

Jan Bom, January 28, 2026