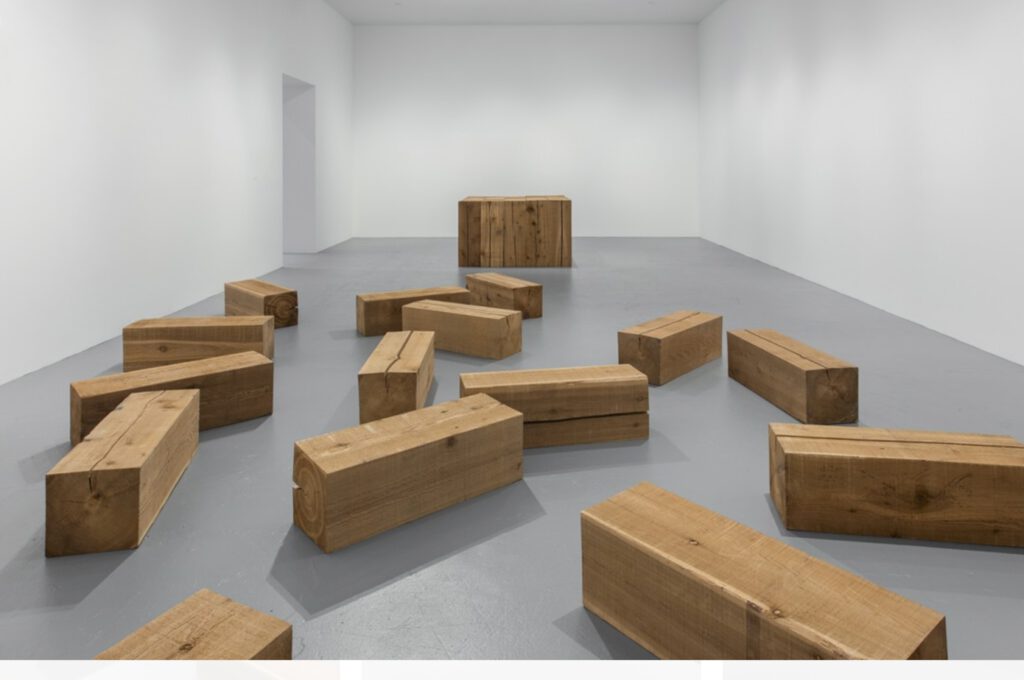

Carl Andre (1935 – 2024) became a master minimalist by stacking unworked wooden beams on top of each other. Or arranging beams like a landscape on the floor. Andre thus created a radically new way of looking at sculptural art. He became one of the founders of minimalism.

One of the raw geometric sculptures by Carl Andre: three loose, stacked rough beams.

With his extremely simple works, the American artist came to be known as one of the founders, if not the founder of minimalism. A major competitor for this title is his friend and former studio mate Frank Stella, who like Andre also died in 2024.

Only once did Andre work a piece of wood with gouge and mallet. In retrospect it is almost a youthful sin, that work from 1959 that he called ‘Last Ladder’. A thick wooden beam with hollowed-out compartments carved into it. It was inspired by the also originally wood-carved ‘Endless Column’ by Constantin Brancusi (1876 – 1957). That had clearly been an inspiration.

No emotion or recognition whatsoever

But Carl Andre went further, by then truly eliminating all elements that could evoke even the slightest emotion or recognition. He also gave no explanation. As his artist friend Frank Stella said to critics: ‘What you see is what you see‘. (It would have been the same Stella who saw Andre’s ‘Last Ladder’, walked around it, stopped at the unworked back and then said: ‘You know, that’s sculpture, too‘.)

His ‘floors’ of wooden blocks (and steel plates and tiles) do bring landscapes to mind. They end on the floor of the hall, but little imagination is needed to extend them further, far beyond the walls of the museum. Brancusi’s column worked the same way. There too the repetition in the sculpture stopped, but his column standing in Romania seems to continue into the clouds. And higher.

Wasn’t Jan Schoonhoven earlier?

I am intrigued by the phenomenon that in both America and Europe almost simultaneously the same idea of minimalism arose, as a counter-reaction to the excessive abstract expressionism (of among others Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock). Simplicity. Rest. Zen. That is what a new generation of artists strived for, who reached for raw, often industrial materials to express this. In the Netherlands Jan Schoonhoven made his first ‘white reliefs’ at the beginning of the sixties. His first famous work was even dated in 1962: R62-1.

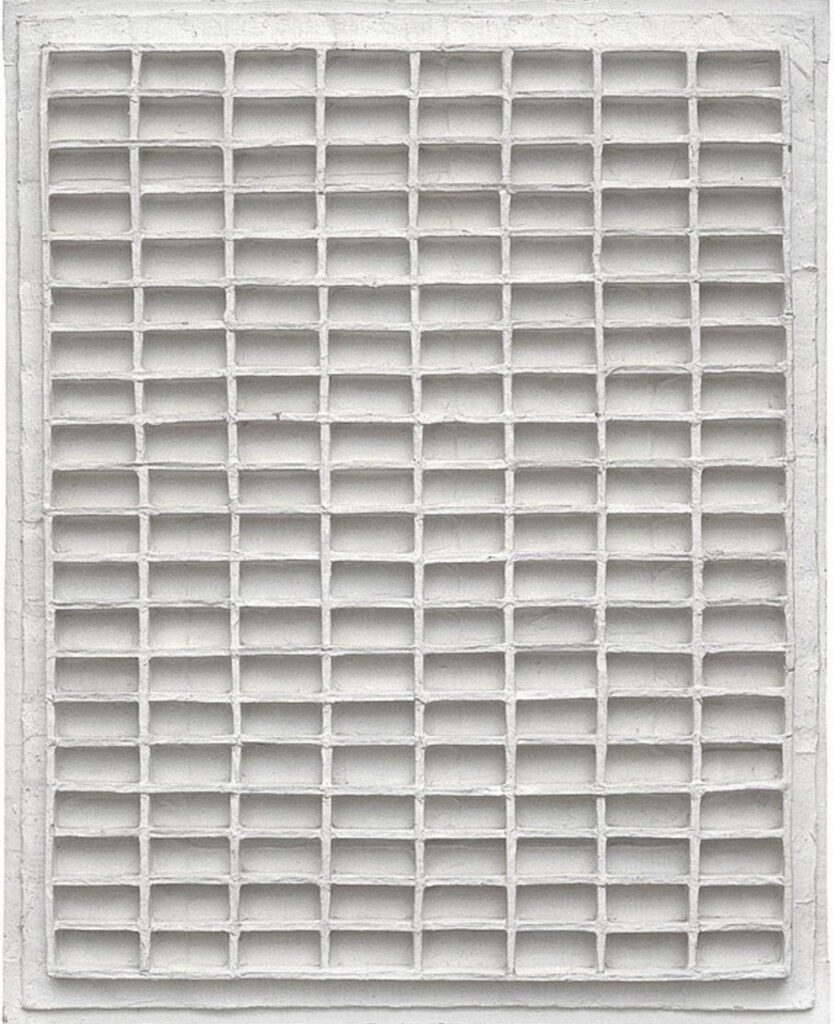

The relief R62-1 by Jan Schoonhoven from 1962.

In that year the Stedelijk Museum presented the work in a group exhibition. It consisted of simple geometric patterns; boxes made of cardboard with a thin layer of white plaster. But the light conjured a beautifully changing play of shadows on it. A new view of Dutch Light was born, totally different from the light and shadow play that Rembrandt captured on his canvases. Schoonhoven had joined the Dutch Nul group, which in turn was inspired by the international Zero movement.

Carl Andre’s first solo exhibition took place only three years after the group exhibition of the Nul movement. And: not in a museum, but in an art gallery. Andre started in 1965 at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York. In the same year the Stedelijk again presented Schoonhoven et al. in a survey exhibition: ZERO – Let Us Explore the Stars.

A definition of minimalism

But Andre’s career shot up much faster. His work was quickly included in exhibitions such as ‘Primary Structures’ (1966) at the Jewish Museum in New York, which helped establish minimalism as an important art movement.

What did the Dutch and the Americans have in common? At least the same definition. Minimalism is an art movement characterized by an extreme form of simplicity and reduction, eliminating all superfluous elements. The goal is to bring out the essence of the artwork by using basic forms, elementary structures, and neutral colors. The emphasis is on the materials and the space itself, rather than on symbolism or emotional expression.

Based on these dates it is thus debatable whether Carl Andre and other Americans were the founders of minimalism. Ideas are simply born simultaneously in different places more often. After that, the question in this case is: who organizes the smartest art marketing? The Stedelijk did everything it could, but still lost the battle to the Yanks.

That doesn’t mean that Andre’s life didn’t make a very deep U-curve. After a personal drama in 1985, when his wife fell out of a window in New York and died, Andre’s career completely collapsed. Even though the artist was acquitted, women continued to accuse him of having pushed her out the window. He himself claimed, later: ‘I was asleep. I was in bed when I heard screaming ‘no, no, no’. According to Andre she must have tried to close the high windows because of the cold, but had lost her balance.

Only long after the legal mud fight did recognition come once more. His beams and other works only came together again in 2013 in New York and then in 2017 in the large survey exhibition ‘Carl Andre, Sculpture as Place, 1958-2010‘ at Moca in Los Angeles. He had had to wait no less than 37 years for it. The penultimate major overview of his oeuvre dated back to 1978-80.

‘The mother of all matter’

Andre kept returning to wood throughout his career, time and again. He called it ‘the mother of all matter’. And in another, rather questionable quote: ‘Like all women who are ravaged by men, wood renews itself by giving and gives itself by renewing’. Recorded by the New Yorker.

Search now on the internet for where minimalism originated, and the answer that appears on the screen is: recognition of the art movement began in the US. Even the editor of the Volkskrant forgot in his obituary of Andre on January 29, 2024 to mention that besides the Americans Donald Judd, Richard Serra, Sol LeWitt and Richard Long there also existed a European group of minimalists. Jan Schoonhoven, Yves Klein, Piero Manzoni and Lucio Fontana; these are not artists of minor renown.

Jan Bom