Georg Baselitz no longer causes a scandal. Not even with a gigantic wooden sculpture of his little sister and her friends who were in the Hitler Youth. Arm in arm they are depicted, in their ‘BDM-Gruppe’. Raw and gigantic. The saw cuts of the chainsaw are still very visible.

That was different in 1980. Then another wooden sculpture by Baselitz of a man rising from a tree trunk caused a gigantic uproar at the Venice Biennale. Baselitz firmly denied, but visitors and critics still really saw someone giving the Hitler salute. Moreover, the painter used black and red brush strokes. Those were the colors of the Nazis. And the roughly carved figure looked just like ‘Der Führer’, with those squinting eyes and that grim mouth. This sculpture ‘Modell für eine Skulptur’ was also on display at Museum Ludwig in Cologne, a private collection of world fame.

What is especially surprising is how vital and original the recent wooden sculptures of the artist are. He is no longer exactly young. Now, in 2023, he is already 85 years old.

He was born in 1938 in the former East German village of Deutschbaselitz, not far from Dresden. He honored the hamlet (of 500 inhabitants) by exchanging his own birth name Hans-Georg Kern for it. The heavy German history would become a common thread in his oeuvre. The themes would even make him one of the most important German artists of his generation, along with contemporaries such as Richter, Polke and not to forget Anselm Kiefer.

Bankruptcy of German pride

The artist was always aware of the violent role Germany played in the last century. His work therefore reflects a double loss. The feeling of social loneliness that was felt by the German population after World War II, but also the bankruptcy of the once so powerful national German pride.

Well into his 70s, in the final phase of his life, he began introducing symbols of eternity into his wooden sculptures. This can be clearly seen in his work from 2011 to 2015 in a collection of them in London. Round shapes, circles that fall like heavy hoops around bodies. They are signs of infinity. A horizontal pole with skulls at the foot and the head: Zero Mobil, 2013-2014, also hung with wooden rings. A marriage of death and eternity.

Baselitz works raw, much more raw than the 20-year younger German Stephan Balkenhol. The difference in years is expressed in a difference between heaviness and lightness. Balkenhol provides humorous commentary on managers in their uniform of white shirt with black trousers. Sculptures from which the wood splinters of the straight chisel still stick out.

Resistance of the wood

Museum Ludwig notes on the website the reason why Baselitz chose wood as a medium, unlike many other artists of his time. Solid wood, from which Baselitz makes his sculptures, was a little appreciated medium in the art world in the last twenty years of the 20th century. And still, although a turning point seems to be on the horizon.

Wood carving stood for Baselitz equal to overcoming the resistance of the material. As he put it himself: “I didn’t want to go where the wood wanted me to go, but in exactly the opposite direction.” Anyone who has ever worked wood themselves understands that Baselitz deliberately ignores the direction of the wood grain. He goes against it with heavy violence. He literally puts the axe in the tree trunk.

Only the chainsaw

Whereas Balkenhol uses the chainsaw to first extract the rough shapes from a tree trunk, Baselitz largely leaves it at that. Smooth finishing of the basic forms with gouges and sandpaper has hardly happened since his scandal sculpture with ‘Hitler salute’.

The idea, and especially the exceptional, is more important to him than a neatly finished presentation. The mechanical saw cuts became a statement in themselves. Brutal. Hard. Industrial. Even with the sculpture of a famous American dancer in Paris: Louise Fuller, a graceful pioneer of modern dance. Height: 3.50 meters. And actually a prototype, intended to be cast in bronze.

The unpolished wood also fits better with his painted works. Those are so coarse that Baselitz became the predecessor of German artists who became known as ‘Die Neue Wilden’. This movement had an international following.

First generation neo-expressionists

Baselitz is therefore classified with his paintings by art critics among the ‘first generation’ neo-expressionists. But his way of operating also later caused ‘liberation of thought’ in a British artist like Tracey Emin.

Baselitz thanked her – and all her sex peers – in his own provocative way. In 2013 he claimed: ‘Women can’t paint as well. That’s a fact’. You can hardly make a more wrong remark than this in these times. Western museums are working hard to retroactively correct the disadvantage of women in visual arts. Stedelijk Museum Schiedam gave Femmy Otten a large solo exhibition in this light, full of female and sexual themes. And: numerous wooden sculptures of lime wood. The condescending remark therefore says more something about Baselitz himself.

The crooked wood of humanity

Baselitz likes to paint his canvases – just like the Jackson Pollock he despises – while they are on the floor. He even started painting with his fingers. To then pesteringly hang them upside down on the wall, whether it was people, landscapes or animals. The result was sometimes surprisingly effective: the German eagle ended up looking upside down like a freshly slaughtered chicken, ready to be plucked.

Baselitz has all in all little faith in humanity. He can therefore identify well with a statement by the philosopher Immanuel Kant (from 1784): ‘Out of the crooked wood of humanity, nothing entirely straight can be built.’

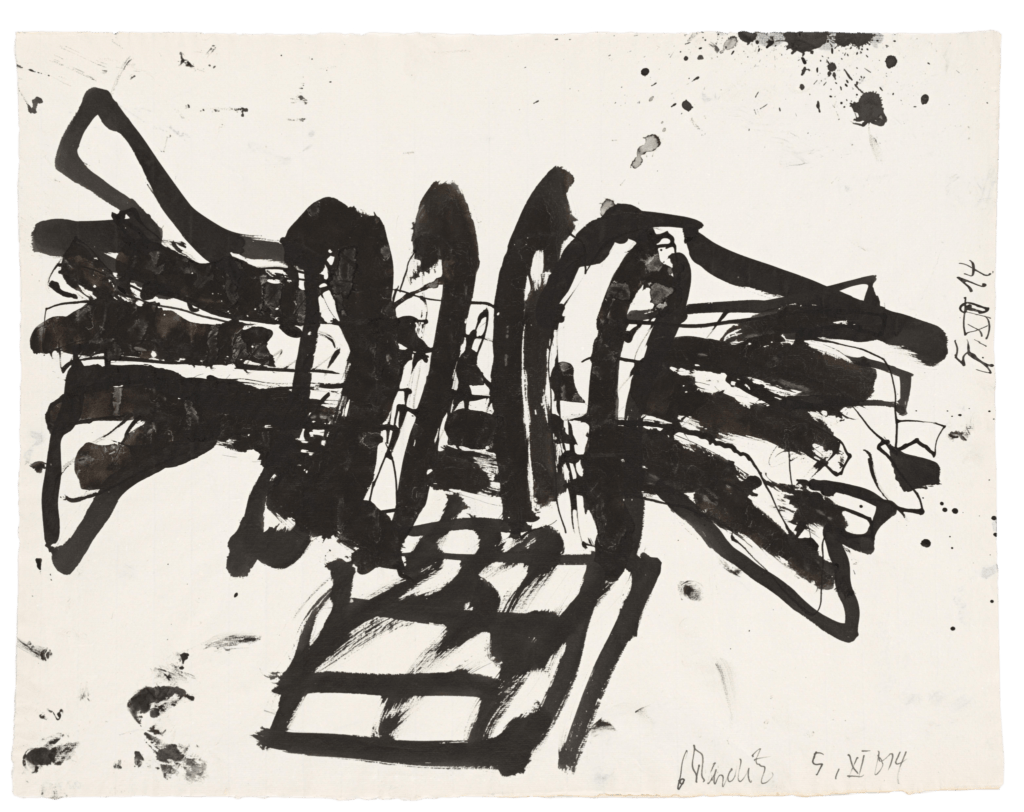

We are back again at trees and nature. The monumental wooden sculptures Baselitz made in the period from 2011 to 2015 can be seen until January 7, 2024 in the (free) Serpentine South gallery and in the Royal Parks in London. Special is that Baselitz also shows the rough sketches there for the first time, which he made while working out the wooden sculptures.