Wild Thing Gauguin, that’s how biographer Sue Prideaux summarizes the famous painter. But she doesn’t forget the wood carver that Gauguin also was. From clog maker to artist who brought back to life the sculptures of the islanders in French Polynesia destroyed by colonizer France.

Wild Thing Gauguin, the first biography about Gauguin in thirty years.

Beautifully how Sue Prideaux sketches the uncompromising character of the young artist Gauguin (1848 – 1903). Searching for a unique painting style on the coast of Brittany, he carved his own clogs. Which he didn’t take off indoors either. Not even after repeated complaints from the downstairs neighbors of the boarding house where he stayed. The clog issue escalated so much that his rent was terminated. He could leave, on his wooden stampers.

Prideaux also describes very precisely how the friendship of Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh in southern French Arles ended in drama. At the height of his nerves, Vincent at some point chased Gauguin on the street with a razor. The Frenchman managed to get away. Only to discover upon returning to their house that the Dutchman had cut off his own ear. The whole house was covered in blood. Could he have prevented this by taking the knife from his friend?

This is how Van Gogh painted his friend Gauguin, at work in their ‘yellow house’ in southern France.

Yet the mutual admiration between these two great artists continued throughout both their lives, even though their paths parted forever after the bloodbath.

Wood carving on Tahiti destroyed

The biographer was able to base her research on, among other things, the handwritten and never published memoirs of Gauguin. He wrote them at the end of his life on the island of Hiva Oa, part of the Marquesas Islands in the South Pacific: Avant et après, dated 1903, the year of his death.

It was in French Polynesia where Gauguin made his most important works in wood. He had hoped to find original sculptures by the islanders there. But alas. They had been almost completely destroyed by the French. The colonizer wanted to make the inhabitants switch from their ‘primitive’ primal religions to Roman Catholicism and Protestantism, two church directions that fought for the most souls. Only on his second trip to the South Pacific did Gauguin see at a stopover in a museum in New Zealand how expressive and imaginative the original wood carving of the Maoris was.

In the art world Gauguin is positioned as the inventor of ‘direct carving‘. This means that for a sculpture carved from wood, no example (to scale) in clay or wax is first made, as was customary in the academic tradition in Europe. But Gauguin was certainly not the first to do this. The original inhabitants had always let themselves be guided by the possibilities offered by a piece of tree trunk. Gauguin adopted that. It’s a point that biographer Prideaux misses in her book, even though she lists numerous other innovations attributed to Gauguin along the way. Among them a range of art movements; from post-impressionism, via symbolism to primitivism.

Fragrant rosewood

She does clear up the misunderstanding that Gauguin had an abundance of fine tropical wood available on Tahiti. That was precisely not the case. All available trees were someone’s property. They had a useful function: if not because the trees bore fruit, then because they offered protection against the fierce tropical sun. But Gauguin wanted to chop. He hadn’t brought his gouges and chisels from France on his long overseas voyage for nothing.

Only high in the mountains of Tahiti did trees grow that belonged to no one. Prideaux describes how Gauguin and his native friend Jotepha began the journey upward early in the morning, both dressed only in a loincloth. Up there they found a group of trees: rosewood. There they felled a tree to drag a thick branch down. From Gauguin’s own notes: ‘The tree smelled of roses… I felt totally peaceful from that moment on. I didn’t strike a blow with the gouge without smelling that scent (noa noa), a fragrance that evoked sweet memories, of victory and of renewal’.

Wild thing Gauguin. Woodcut ‘The universe is being created’ from the Noa Noa series.

He wrote it down himself in his book Noa Noa, upon his return to Paris in 1893. He wanted to arouse interest in his home country for the lost paradise, as he had found it. No longer a Garden of Eden, but a colony that with the slogans of the French Revolution oppressed precisely a freedom-loving people. Under the same title Noa Noa Gauguin also made a substantial series of woodcuts with a strong symbolic and narrative character. What was special was that he perversely told the Polynesian creation story from right to left.

In Paris he showed, in addition to 42 paintings, also a sculpture of the mother god Hina and her son Fatu, carved in 1892. Large heads, claw-like hands, exactly like the ‘Tikis‘ depicted their gods themselves. Prideaux: ‘These wood carvings were possibly the most provocative items in the show.’ They were far outside the tradition of Western sculpture.

Last place of residence: Hiva Oa

On his second and last trip to the South Pacific, Gauguin moved even further away, to the Marquesas Islands. Here, on Hiva Oa, he found more of the old culture of the islanders than on Tahiti, even though the original population on this island also had to organize traditional rituals in secret. Human sacrifices were no longer made, certainly no child sacrifices. Those had become very precious with a strongly decimating population.

Gauguin had a house built there according to his own design, which he called Maison du Jouir. He wanted to annoy both the clergy and the local French authorities with that name. It was not a pleasure house or brothel, but Gauguin did take in a young mistress and a beautiful red-haired model for his paintings. The trio didn’t take Western ideas about marital fidelity too seriously. Neither did the other native visitors, who celebrated exuberantly in the house.

Wild Thing Gauguin

In the praise of Gauguin, admirer of strong women like his grandmother and his legal Danish wife Mette, biographer Prideaux is not very critical of the painter when it comes to the young age of his new lovers. Without her own comment she dryly notes how Gauguin went looking for a new woman. ‘He found her in a village (-) further on where her father, Hapa, was village chief. She was called Vaeoho Marie-Rose and she was probably 14 years old. She was happy to go with Gauguin, in exchange for a roll of 31 meters of cotton and a sewing machine of 200 francs, bought in the local shop of Ben Varney.’

Gauguin’s self-carved walking stick, with a female nude on the handle.

Today a storm of criticism would arise on social media, if an artist repeatedly took a minor girl as a mistress into his home. Isn’t that called pedophilia? Prideaux doesn’t just let the reader draw this conclusion themselves, but takes ample space to describe the context of the free sexual culture of the islanders of that time, a culture of polygamy.

Remarkable: one of the reasons for writing the biography was precisely the uproar that arose when visitors and critics of a retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery in Australia (and the National Gallery in London) loudly protested against the ‘pedophile Gauguin’. Prideaux makes no mention of this in the biography. She even goes one better, by describing in detail how Gauguin walked around the island with a walking stick that he had carved at the top with a buxom nude girl.

The hypocritical bishop

Also again to provoke his French compatriots, Gauguin decorated his new house at the entrance with two pillars. One of them depicted the local bishop Martin. He provided the clergyman’s head with two devil’s horns. The other sculpture of 66 centimeters height was that of the native woman Thérèse. The bishop secretly maintained a sexual relationship with this housekeeper – the whole island chuckled at so much hypocrisy, because everyone knew about it.

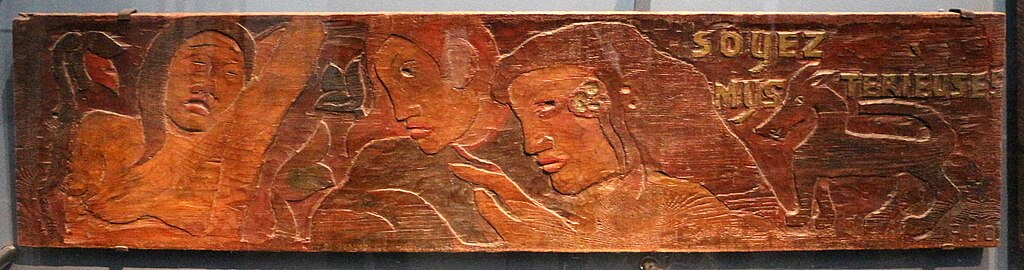

A wooden relief in Gauguin’s last house: Soyez amoureuses et vous serez heureuses.

Inside the house Gauguin had made reliefs of, among others, Taaroa, the Polynesian god of creation. On door posts the figures of native naked women, on horizontal panels women with texts like: Soyez amoureuses et vous serez heureuses (Be in love and you will be happy).

This time he used no native wood, but sequoia, which had arrived on the island as packaging wood. In the sculptures the holes of nails can still be seen. The sculpture of Thérèse went under the hammer at Christie’s auction house in 2015 for 30.9 million dollars.

The grave of Gauguin, with a self-fired clay sculpture (now a copy) of the Polynesian goddess Oviri.

Gauguin’s health deteriorated sharply after a last revival. He suffered unbearable pain from a badly set leg fracture and incurable wounds, caused after a fight with fishermen in France. The amounts of morphine and laudanum he took as painkillers kept growing.

Wild Thing Gauguin. After his death at 55 years of age, his great adversary, Bishop Martin, kidnapped his body to bury it in a flash at the Catholic cemetery, above the town of Atuona. With a cross on the grave. Completely against the artist’s will. But Gauguin had the last laugh after all. On his grave his somewhat gruesome cross-eyed sculpture of Oviri was placed, the Polynesian goddess of mourning and sorrow. (Oviri is also Tahitian for ‘wild‘ and ‘savage‘) When the bishop himself died later, his grave would permanently look out at this ‘idol’. Not much later, the Belgian chansonnier Jacques Brel would also find his final resting place on the same cemetery, a few meters away.

Jan Bom, May 26, 2025

I read ‘Wild Thing, a life of Paul Gauguin’ in the original English version by Sue Prideaux from 2024. In 2025 a Dutch translation was published by De Arbeiderspers: Wildeman. Both books can be ordered at bookstores or on the internet, including at Bol.com.